There was Luna the orphaned orca who sought the company of people — and died as a result after being savaged by a tugboat’s propeller.

Springer, another orphan captured and then successfully released back to her pod.

And Tilikum, the orca blamed for killing a trainer at a Victoria tourist attraction — and subsequently two other people — who became the subject for the powerful documentary Blackfish.

Orcas have captured British Columbians’ attention and highlighted issues of conservation and the morality of keeping such intelligent, social creatures in captivity.

Author Mark Leiren-Young’s The Killer Whale Who Changed The World looks at the tragic story of Moby Doll, the first captive killer whale to be put on display. It’s a story that unfolds in the Salish Sea and Vancouver.

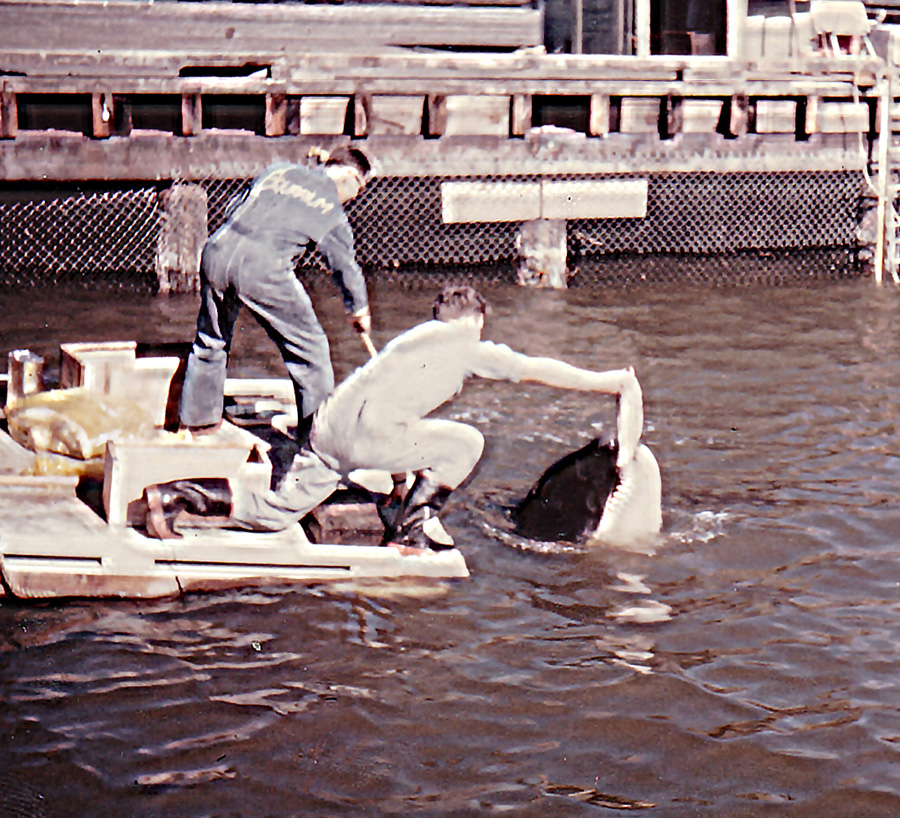

Moby Doll was supposed to be dead. In 1964, Murray Newman, the founding director of the Vancouver Aquarium, wanted to display a full-size replica of an orca — and for that he needed a dead whale as a model.

But things changed drastically when the harpooned whale didn’t die. Newman put the 4.3-metre-long male in a pen at Burrard Dry Docks, where he attracted worldwide attention and drew the curious public.

Until Moby Doll died three months later.

If you love animals, or Vancouver, this book is worth your time. It’s a captivating read and Leiren-Young’s passion for the issues — our relationship with other species, and the environment — drives the narrative.

I’m not going to lie, I felt more and more like a hippy with each passing page. As I read how these “monsters” were treated in captivity, I envisioned myself on the front lines of some protest with a picket sign in hand and a beard halfway down my chest. As I learned about how we used to attack orcas in the oceans, I imagined joining the Sea Shepherd Society’s radical seafaring activists.

Leiren-Young writes about our fear of the unknown. And whales, hard to study and often feared, were big unknowns 50 years ago.

But reading about public attitudes of the time made my blood boil.

The Tyee interviewed Leiren-Young about the book and his thoughts on orcas. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: Where did your inspiration to write the book come from?

Leiren-Young: The idea that the first ever killer whale displayed in captivity was in Vancouver kind of blew my mind, and I wanted to know more about it. I actually, with no assignment, decided I was going to write it. I remember meeting Murray Newman, and I asked ‘Why would anyone ever think of killing a killer whale, why would anyone want to hurt this magnificent creature?’ He picked up a book and read a passage that sounded like he was describing the scariest sea monster of all time, and it was about a killer whale. It was from 1964, published just months before his expedition. I went ‘OK, how did I not know about this?’ So it just really stuck with me. I don’t know if I’ve ever had a story stick with me for this long.

How did the moment when Moby was captured set the stage for how British Columbians feel about whales. How did Moby shape that?

I think that Vancouver just became the first place to see a killer whale up close. This can’t be a coincidence that Vancouver is the birthplace of the whale hunting movement and also the birthplace of Greenpeace and, by an extension, Sea Shepherd. Paul Spong, the person who convinced Greenpeace that they should look beyond an anti-nuke association and start focusing on whales, happened to work for the Vancouver Aquarium. But the wonderful eureka moment for me interviewing Spong was when I asked him a question I ask everybody — ‘Tell me about the first time you saw a whale.’ He rocked my world when he said the first time he saw a whale was Moby Doll’s brain. He looked at this huge preserved brain and thought ‘There’s something here, there’s something to this in this incredibly huge brain.’ Spong was that straight line between Greenpeace and ‘save the whales’ and Spong’s first encounter was Moby Doll.

How do you think Moby Doll created the culture of loving whales in B.C.?

Moby was the paradigm shift. When Moby didn’t behave the way the media expected, everything shifted. I was able to read every script for every television newscast through the period of 1964 from when the hunt went out to when Moby died. The night Moby was caught, the anchor on CBC News reported ‘captured a monster.’ That was the word they used. And within the span of roughly 48 hours, when the whale didn’t do anything monstrous, the coverage completely shifted. From when Moby was called a monster to when Moby was called ‘Vancouver’s pet whale’ was just a few days.

Do you think the fact that Moby Doll was a southern resident whale had any impact on public perception?

In 1964, nobody knew there were different kinds of killer whales. Several whale experts said that if Moby had been a transient, and peeled the skin off a seal in front of spectators, it would have confirmed all those fears and nightmares. If instead of the whale just looking for chinook, you had a whale that was taking out a seal, it would have been a very different perception. When people think of killer whales, they really just imagine the southern residents and the chatty pods.

How do you feel about the name “killer whale?” Do you prefer to use “orca?”

You’ve probably had the lecture that the correct term is killer whale, but I am totally with Paul Spong and his logic. I really love his comment — ‘If you’re going to call them killer whales you should call us killer apes.’

How do you feel about animals in captivity?

It’s tough, because I’m definitely not a fan. I understand the history of it and why it mattered historically, especially when we’re talking about orcas. Almost everyone who went out and studied orcas made these discoveries because they were in tanks. But almost all of those discoveries were because of what those tanks were doing to the orcas. So I’m not a fan. But there are some animals that are on the verge of extinction, and what do you do to preserve a species?

What about when animals are captured for captive breeding?

There are only 83 southern residents in the wild, and we are one Kinder Morgan accident away from having none, so I am really trying to put my focus on the whales in the wild.

How do you think we can promote wonder and awe without also harming the animals that we are looking to protect?

I think it’s getting those orcas on our screens and getting word out. I wrote this book to help people fall in love with orcas. I hope that we can do this trick with the media. I love the movement towards terrestrial whale watching, where you watch them from shore rather than chase them around. I have had conversations with the top whale experts who are fond of better whale watching groups — the people that keep their distance. You know, I was out on one boat and I saw some drones harassing whales.

It’s funny you mention media as the driving force to inspire young minds. I have never been to a zoo in my life, and my interest in orcas and other mammals all stemmed from watching them on television.

I was in love with these things from the moment I saw them on TV. I’ve interviewed people for documentaries who traced their interest back to Free Willy. They saw Free Willy and suddenly they were going to be whale experts. I think that the media can make magic.

Do you think orca rights or orca personhood can ever be a possibility in a world where humans always put themselves first?

It’s a really interesting question. I keep going back to thinking ‘OK, but what can we actually do to protect the habitat and protect the culture that is disappearing?’ If orcas were accorded any type of legal rights, then it becomes very difficult to approve things that can damage them. The National Energy Board [report] on Kinder Morgan references the southern resident population and says that it’s very clear that expansion will be very bad for the whales — and that’s not even taking into account the possibility of a spill. It’s just about the increased tanker traffic that can potentially be really dangerous to a population that’s considered endangered. How do you protect that population? Maybe you give them rights.

So you believe that orcas are on an equal footing with us?

I am curious to find a justification as to why they are not. I couldn’t find one. I was asking people ‘what is it that makes a human human?’ and the answer seems very vague. Every answer seems to apply to an orca. I understand the economic justification for not making them equal. If orcas were suddenly accorded the same rights as us, the global economy collapses. If you accord them even basic rights, that means that it keeps them alive and saves the species. It’s not just about the species of orcas, it’s the individual cultures that are fascinating. We’ve already wiped out one pod in Alaska, and with it an entire culture.

What was your biggest challenge in writing this book?

Reconciling all of the information. I was working from so many people’s different memories, and so many memories had been shaped by myth. Even at the time, the newspapers were constantly contradicting each other. When you read a story on Moby Doll, almost everything you read published in the last few decades talks about how no one knew what to feed this whale and that people tried all these wacky things before they finally, magically, tried a salmon. But if you go back to those very first news stories in July 1964, the very first thing they tried to feed that whale was salmon. The story just shifted to the ‘cute’ version where they had no clue.

What did you want to put in the book, but couldn’t?

I would have loved to spend more time on the whales of today. I got past Moby and wanted to keep researching everything. I wanted to know more about their culture. What I wanted to know was ‘what’s happening now, how can we keep these orcas alive?’

My Holy Grail is that I have been told repeatedly that there its footage of the one day Moby was on display and I have yet to find it.

What do you want the take-home message to be?

I’m going to sound so terribly B.C. here — but what pops into my mind is ‘SAVE THE WHALES, SAVE THE WHALES, SAVE THE WHALES!’

What’s next on this story?

We’re in post-production for two documentaries. One is on Granny, the 100-year-old whale, and the other is a feature documentary on Moby. I’m not done with the whales yet.

The Killer Whale Who Changed the World is forthcoming from Greystone Books, with a release date of Sept. 17. Its Vancouver launch is scheduled for Sept. 26 at 7 p.m. at Cottage Bistro, 4468 Main St. A Victoria book launch will be held at Bolen Books at 7:30 p.m. on Oct. 3. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: