On May 31, 1982, following years of protests against a BC Hydro power project criticized for causing ecological damage, the anarchist collective Direct Action blew up a BC Hydro substation on Vancouver Island. “We reject both the ecological destruction and the human oppression inherent in the industrial societies of the corporate machine in the West and the Communist machine in the East,” they wrote in a statement claiming responsibility for the attack. “This is the best contribution we can make towards protecting the Earth.”

The bombing caused $5 million in damages and divided B.C. environmentalists. It was the first high-profile act of sabotage undertaken by a group of Vancouver-based guerillas who aimed to radicalize the political landscape. Frustrated by the slow progress and ineffectiveness of traditional forms of activism, Direct Action (who would later become known as the Vancouver Five or the Squamish Five) embarked on a series of bombings and arson in the name, they said, of environmentalism, anti-militarism and feminism.

In October 1982, five months after dynamiting the power station, the group drove a truck containing dynamite from Vancouver to Toronto and bombed a Litton Systems plant that was producing parts for American cruise missile components. Ten employees were injured when the bombs detonated before the building could be evacuated. In November 1982, two members joined with another group to create the Wimmin’s Fire Brigade, and firebombed three Red Hot Video pornography stores in the Lower Mainland that stocked violent pornographic films, claiming self-defence against hate propaganda.

In January 1983, the five were apprehended by an RCMP unit disguised as highway workers just south of Squamish (giving rise to the name “Squamish Five” that media dubbed the group). Following a contentious trial that was publicized worldwide, each member received a jail sentence ranging from six years to life.

The group’s concerns over industrialization and ecological degradation mirror the concerns we see today over pipelines and liquefied natural gas, says historian Eryk Martin, who recently completed his PhD on the history of anarchist movements in Vancouver, focusing on the experiences of the Vancouver Five. Martin will speak on the subject this Thursday, Oct. 27 at 7:30 p.m. at the Museum of Vancouver. Part of the Vancouver Historical Society speaker series, the talk is free and open to the public and will be followed by a Q&A.

We spoke to Martin in advance of his talk about the history of radical activism in Vancouver and the legacy of the Vancouver Five.

The Tyee: How did you become interested in the history of anarchism and radical activism in Vancouver?

Eryk Martin: The topic of radical social movements was interesting to me because it seemed to conflict with almost every traditional image of Canadian history I’d ever come across as a young person. I think there is often this idea — particularly among people of relative privilege — that Canada is a peaceful place with a peaceful past. That’s simply not true. And as a result, the more examples I came across that disrupted that myth, the more interested I became in social violence and radical activism.

At the end of 1990s and early 2000s, there was a resurgence of anarchism within the anti-globalization movement and I wanted to know where this anarchism came from, what its origins were. I started to poke into local histories of anarchism and found a constant reference to Direct Action, the Wimmin’s Fire Brigade and these people called the Vancouver Five. In terms of academic historians, nobody had really done anything on this, so that’s what made me want to pick it up.

What were the main issues that concerned radical activists in 1970s and ‘80s Vancouver?

One of the most amazing things about that time period is the diversity of activist struggles. Racism and the legacies of colonialism; patriarchy and homophobia; capitalism, poverty, and the dismantling of social services; environmental issues of all kinds; the prison-industrial complex; Canada’s contribution to militarism and the Cold War: these were just some of the issues that shaped the political landscape of Vancouver in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Vancouver Five were committed to anti-hierarchical politics and were highly concerned about the expansion of industrialization in British Columbia. They feared the expansion of the power grid, more dams and more power lines would create the infrastructure for other environmentally damaging forms of industry. They also had social concerns that were environmental from a different perspective — they were concerned about Indigenous access to land. Their critiques of BC Hydro and how that can lead to further industrialization mirrors the debates going on right now about pipelines and different aspects of the oil and gas industry.

Why did the Vancouver Five believe industrial sabotage was the best way to achieve their goals?

They never argued sabotage was the only way to make political change, but they believed social movements could benefit from having a wing or front that was willing to take up sabotage. They believed people should have recourse to it as a last resort. In all three of their high-profile acts of sabotage, they used sabotage because they — and others — had failed to change things through other means. They argued sabotage should be used when the ramifications of not acting are incredibly dire. For example, they argued if you don’t act against the proliferation of nuclear weapons, you could see the end of the world. If you don’t act on industrialization, you’re going to see catastrophic environmental change. They thought the costs of not acting are too high to do nothing.

Historian Gordon Hak has said that even among the vast majority of leftists, the actions of the Vancouver Five were “beyond the pale.” What did you uncover about public reactions to the Vancouver Five?

Each of the actions received different responses. The bombing of Litton systems was widely condemned in part because of injuries that took place as a result of that bombing. But the arsons of Red Hot Video were much more supported. When Wimmin’s Fire Brigade released their statement saying it was an act of self-defence against hate propaganda, the BC Federation of Women released a statement empathizing with the anger and frustration contained in their actions. When called upon to comment, many women’s groups refused to criticize the Wimmin’s Fire Brigade and focused on the limits of the police, arguing the films stocked by Red Hot Video were in violation of legal guidelines. There was much more public support for that campaign because the debate around pornography was tied strongly to debates about violence against women.

How did left-wing activists in the 1970s and ‘80s draw from or depart from earlier waves of activism in B.C.?

One thing that linked different generations of activists was a rigorous debate over tactics. Should activists use the ballot box, the general strike, or a seizure of the state through force? These questions could be found in leftist circles both at the beginning and end of the 20th century. Of course, many things also changed. One of the most obvious was the growing awareness of environmental change. This provided a new sense of urgency to activist politics, and that urgency in turn shaped both an assessment of environmental problems and their proposed solutions.

The Vancouver Five were distinct in that most of the left-wing armed groups we tend to think about in the late 20th century embraced a communist perspective of one sort or another. The Vancouver Five, however, were anarchists. That said, for various reasons, they tended not to use that label very often. One reason for that was the public’s perception of anarchism and how the media’s depiction of anarchism drew on crude stereotypes. And that tendency to avoid sectarian affiliations and firm ideological identities might also be something that separated them off from other clandestine movements. After all, embracing and performing ideology as part of your identity was a common phenomenon within the left.

What legacy did radical left-wing movements of this period leave behind?

They have contributed directly to the political activism of the present. Many of the activists or institutions that are fighting against the legacies of colonialism, or against poverty and gentrification, or for LGBTQ2 rights and liberation began that work in the 1970s and 1980s. So there’s a direct link between then and now, even if the contours of that activism has changed over time.

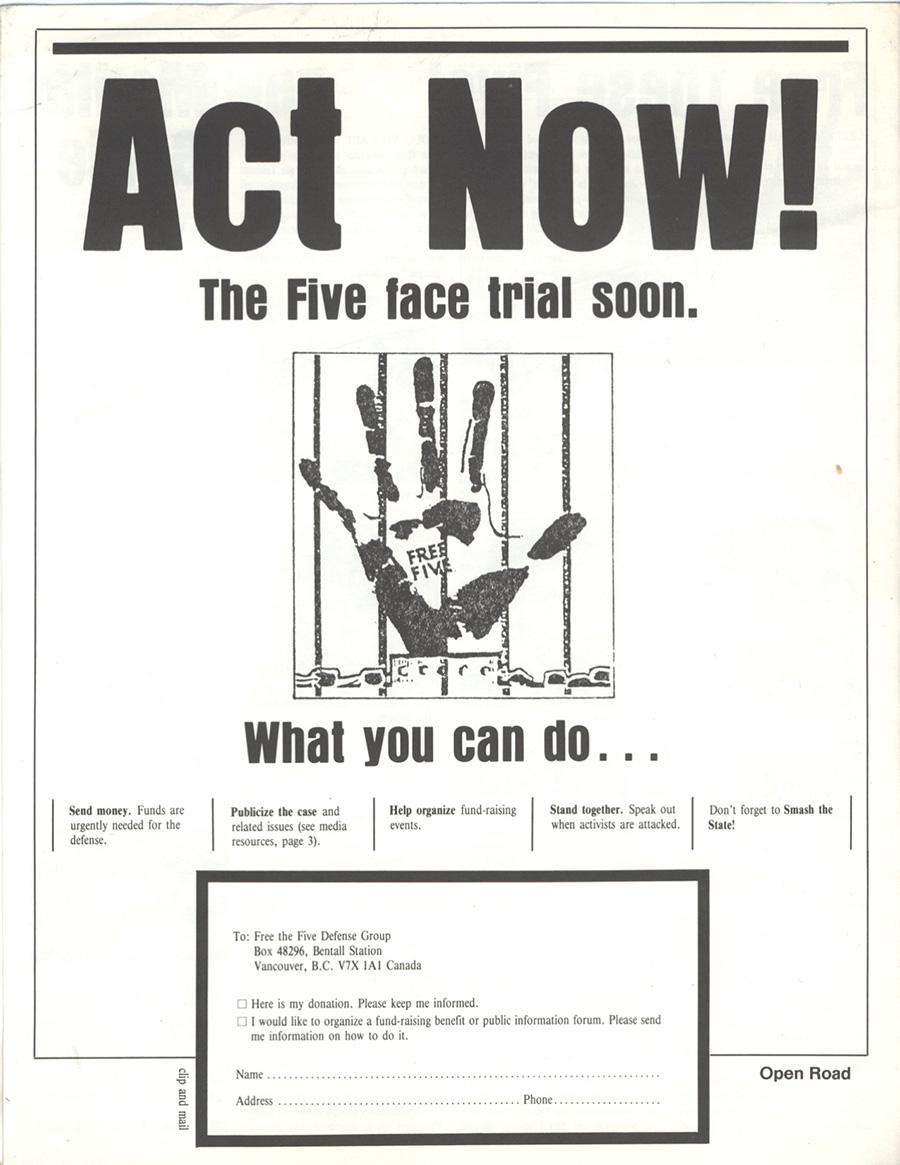

The trial of the Vancouver Five was the starting point for a new generation of anarchists. Many people learned about anarchism because of public conversations taking place around the trial. Many got involved in “Free the Five” committees — they sprung up all over the country. People raised money to help cover court costs or critique what they saw as abuses in the press or different issues surrounding the trial itself. Over the long term, those early moments of organizing helped create a new generation of anarchists. The trial directly contributed to the maintenance and continuation of anarchism particularly in Vancouver.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Eryk Martin will give a lecture on “Direct Action: Left Wing Activism in the 1970s and 1980s” this Thursday, Oct. 27, 7:30 p.m. at the Museum of Vancouver. The talk, part of the Vancouver Historical Society speaker series, is free and open to the public. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: