[Editor's note: In this Tyee Solutions Society series, reporter Chris Wood profiles what death row looks like for endangered species and their landscapes in three Canadian provinces.]

The hum of midday traffic penetrates the August foliage, adding to the dense buzz of insect life filling the air above a pond. Green discs of lily pads make geometric art on its sheltered surface; darting, electric blue dragonflies dance along it. On a fallen tree acting as a grey ramp from the water, short legs propel a high-domed brown shell into the sun. There it settles, and an ancient-looking head emerges, stretching to expose a long, lemon-yellow throat. For this Blanding's Turtle, barely middle-aged at 30, death row is a bright clearing in the woods not far from the Detroit River.

Viewed from the air or on a map, the turtle's prison appears as one of five patches of green squeezed between expressways and the former Windsor, Ontario, raceway, a few kilometres from Canada's busiest truck crossing into the United States at the Ambassador Bridge and adjacent to a second crossing being built at a cost of $1 billion.

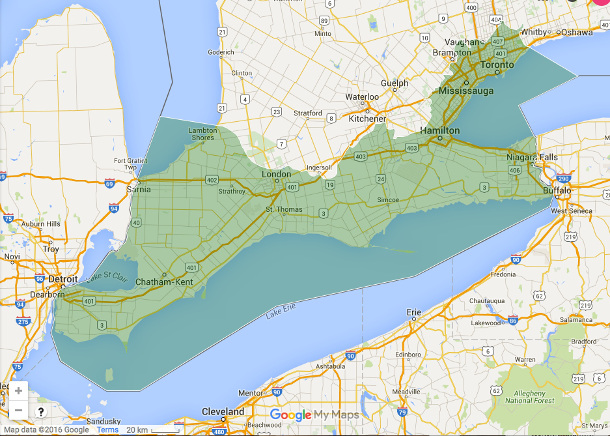

The not-quite-contiguous patches of green known collectively as the Ojibway Prairie Complex, a fractured mosaic altogether fewer than 250 hectares in area, five kilometres long and three at the widest, were once part of a richly varied landscape of hardwood forests, grassland prairie and wetlands that stretched unbroken from here to the St. Lawrence River at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, and as far north as the granite border of the Canadian Shield.

The southern fringe of that ancient forest, a region encompassing most of today's southern Ontario, known as the Carolinian forest ecosystem, is now Canada's most reduced and vulnerable landscape.

Historically, the ancient forest was far from unpopulated. Tens of thousands of people lived and farmed under its eaves, including members of the Haudenosaunee (sometimes called the Iroquois) Confederacy, whose political sophistication influenced the writing of the U.S. Constitution.

It was not, however, fenced every few hundred meters in barbed wire or squared by concession roads, let alone bisected from east to west by a continuous asphalt barrier 40 metres wide, travelled 24/7 by speeding motor vehicles. Lynx, cougar, moose, wolverines and bear roamed freely from Lake Erie to Lake Huron to the Ottawa River.

When Europeans arrived to settle in the 19th century, the forest and its unfamiliar wildlife inspired fear. "Progress was clearing," says Scott Gillingwater, staff species-at-risk biologist for the Upper Thames R. Conservation Authority and an advisor to Canada's committee that identifies endangered species. "It created opportunity. It created money."

It also drove back the "ferocious" wildlife. Hunters slaughtered 400 black bears in the neighbourhood of Point Pelee in a single season in the 1800s. Now, apart from the occasional stray individual, no breeding population of most of the large mammals that formerly occupied the Carolinian landscape remain. "No bears, no moose, no bobcats. A few beaver," Gillingwater notes.

Within the shreds and scraps

Fly across southern Ontario today and the occasional woodlot or tree line along a stream are about all that remain of the Carolinian ecosystem. Other shreds hang on along the serpentine Niagara Escarpment, which runs from the famous falls where water from Lake Erie flows over its edge, all the way to the Tobermory Peninsula between Georgian Bay and Lake Huron.

The rest is mostly gone: long ago turned into farmland or, in the last half-century, the housing that has sprawled ever further beyond the city limits of Toronto, Hamilton, London and Windsor. Less than 15 per cent of the Carolinian's former extent remains.

The scraps left behind, like the six hanging on at Windsor's western edge, are usually fragmented and small, all "edge," as biologists say, with little to none of the biologically diverse and protected "interior" that many animals require for both safety and adequate prey or other food.

With those scraps separated often by dozens if not hundreds of kilometres, opportunities for meeting and mating between small remnant communities of endangered animals are blocked by human barriers -- most notably roadways, with their lethal-to-wildlife vehicle traffic. For reptiles and amphibians in particular, "[Highway] 401 is the ultimate barrier, except for a couple of rivers and culverts that go below it," Gillingwater says.

"So you're getting genetic isolation," the naturalist warns, "because these animals have been separated into small areas and there's no realistic opportunity for animals to move between these for genetic refreshment."

Such biogenetic "island" effects are especially hard on turtles, which grow slowly, live long and, like people, do not become reproductively capable until their teens. Even then, says Gillingwater, an adult snapping turtle may need to live 80 to 90 years to replace herself and her mate.

"What worked for them for millions of years of living long is not working for them any more," he adds, "because adults are being killed on roads, shot with shotguns, hooked with fishing lines."

One population of spiny softshell turtles that Gillingwater has studied for 15 years has seen the number of females nesting each season fall by half in that time. "That is a pretty scary scenario for an animal that really should do quite well."

Snakes, cold-blooded creatures that, like turtles, depend on the sun's heat to activate their metabolism, risk being crushed by tires while sunning themselves on pavement -- or simply killed by humans responding to emotional revulsion. Ontario's most threatened snakes are its largest -- the Eastern Gray Rat Snake, which can reach over two metres in length -- and the Massasauga Rattlesnake, Canada's only venomous snake.

'Little oases of habitat'

The conversion of the great Carolinian wetland-prairie-forest ecosystem into the country's most densely populated region -- 10 million people, nearly one Canadian in three, now live there -- has increased the pressure on those few communities of original wildlife still hanging on in other ways.

As Gillingwater puts it, garbage and fields of corn and soybeans now "subsidize" flourishing populations of coyotes, raccoons and skunks, happy to return to traditional diets of smaller animals -- such as turtle eggs and young snakes -- when those human leftovers are unavailable.

"The landscape has been so manipulated, for so many years," he says, "it's amazing these animals are still here."

For how much longer they'll stay is an open question. "I call these little oases of habitat," Gillingwater says of Windsor's broken string of semi-protected areas. "This is their only remaining habitat. It doesn't mean they're free from threat."

Indeed, the few snippets of landscape left to the snakes and turtles at Ontario's southwestern tip, continue to be chewed away from them.

The approach lanes to the new Canada-U.S. bridge over the Detroit R., to be named after hockey hero Gordie Howe, are being installed along one edge of the preserves. At another, a scrap of undeveloped land that for now connects the parcels of protected ecosystem to the bank of the Detroit River is being eyed for port development.

In December, Ontario's Municipal Board approved an application from a numbered company to develop a big box store where the Windsor Raceway used to be. As part of a deal to end 13 years of resistance to the project, 1223244 Ont. Ltd. agreed to turn 4.1 hectares of property adjoining the protected areas over to the city, to be restored as "natural heritage space." The gift will benefit the refuge's snakes, the regulator ruled, more than a sharp jump in traffic on nearby streets will increase their road mortality.

The Carolinian didn't end at the Detroit River or Great Lakes, of course. It stretched far south into what are now Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and the U.S. northeast. Protected scraps of forest and snippets of tall-grass prairie, along with their resident reptile and other species, hold on there as well.

And small steps might still be taken to relieve the pressure on the Ojibway Prairie complex. Windsor's mayor has pushed to protect its last ecological connection to the water artery of the Detroit River. Traffic might be re-routed by a kilometre or two and streets torn up to reconnect its fragments, though that's not on any public agenda.

In any case, for the Blanding's Turtle and its Snapping and Softshell cousins, for the Massasauga Rattler and its Rat Snake relative, for the darting electric blue dragonflies and other refugee species clinging to existence around the sun-dappled pond in the woods, "it's not one thing," Gillingwater says. "It's not 10 things. It's humans."

More and more often, his outlook for the inmates of this wing of nature's death row is pessimistic. "There's no way they'll survive." ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: