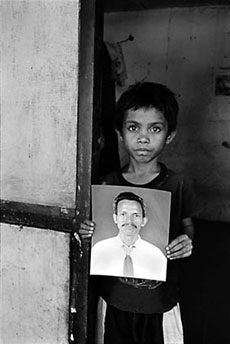

[These photos are from East Timor: Testimony by Vancouver photojournalist Elaine Briere, with essays by Noam Chomsky and others. Here, she describes her 30-year involvement with the people of that strife-torn nation, now rebuilding.]

In 1974, I was traveling with a friend, following the "hippie trail," and intending to visit a number of countries in Southeast Asia. We arrived by small plane and landed on a dirt airstrip in, what seemed like, the middle of nowhere. We found a beautiful country with its indigenous culture still fully intact. East Timor had been a Portuguese colony for many years but the colonization had little impact on the people's way of life.

There was a trading post in the capital, Dili, but the Portuguese had not really penetrated the interior. The Timorese had a long history of resisting malai (foreigners). We only stayed for two weeks, but had I known then what I learned later in my travels, I would have stayed much longer. I didn't fully appreciate the beauty and specialness of the country and people until we had moved on to Indonesia and Thailand, where western influences were so much greater. In these countries, the people had, for the most part, lost their old way of life - the economic base had changed, and the people seemed to have lost a sense of confidence in their traditions. East Timor had remained much more isolated and had fully retained its own culture and subsistence farming economy.

At the time, the Carnation Revolution had just taken place in Portugal and the imperialist Salazar-Caetano government had been overthrown. This was a big turning point for the people of East Timor, as they thought they would regain independence. However, on December 7, 1975, Indonesia launched a brutal land, sea, and air invasion, which, by their own definition, was referred to as the "blitzkrieg." Their slogan for the invasion was "Breakfast at Dili, lunch at Baucau"!

Sheer brutality

The terror tactics used and the sheer brutality of the invaders was beyond imagination. Some of the people fled from the city to the hillsides but many stayed and were wholly unprepared for the level of violence that ensued. There were no military targets; there was just indiscriminant killing. The troops ran amok, gunning people down in the streets and lobbing grenades into the houses. When the people would offer food to the troops to placate them, the Indonesians would take what was offered, then kill them. The troops were poorly paid and their reward for service was what they could plunder.

Indonesia justified the invasion to the West by portraying it as an anti-communist campaign. East Timor's ruling, populist, Fretilin party did have a Marxist element to it, but that was quite common in those days. The people of East Timor had historically worked on a co-operative model of agriculture. There had been a brief civil war before the invasion but there are always quibbling elements during the formation of a new independent state. In fact, Indonesia had fomented unrest by bribing one of the political parties to attack Fretilin. Indonesia invaded on the pretext of stopping a civil war, but this brief unrest had been over for months. Fretilin was running the country very competently, and overseas aid organizations had given the government very high marks for their progress.

The invasion bogged down very quickly after Dili was devastated. The troops couldn't get beyond Baucau into the interior. Though they had an overwhelming advantage in terms of firepower, the Timorese managed to fight back, using spears and outdated weapons that the Portuguese had left behind. By late 1976, there was a standstill. US president Carter then lifted an arms embargo against countries in conflict to make a special sale to Indonesia. It received sixteen counter-insurgency aircraft (the type used in Vietnam) that could fly very low and proceeded to drop defoliants and cluster bombs. It adopted a scorched-earth policy that, of course, was highly effective. The death toll was enormous. People had to flee to the mountains; much of the farmland and forest was destroyed. It was a strategy of starvation.

Global turning point

No foreigners were allowed in until late 1978, when the Red Cross was given access to try to deal with the mass starvation taking place. In the meantime, Indonesia set about exploiting what little resources were left.

In 1980 the resistance recouped and attacked an army base. This led to another campaign of terror, and so continued the pattern, where, every two to three years, another offensive was launched. Troops would march through the villages and countryside, forcibly recruiting male villagers, thus leaving fewer and fewer people to plant crops; so the cycle of starvation continued.

Very little of this information reached the outside world. There was enormous pressure from human rights groups to open the borders to outsiders. By 1989, more news started to trickle out, mostly through Catholic Church avenues. But it wasn't until the Dili massacre in 1991, where Indonesians attacked students seeking safety in the churches, that the Catholic Church became more active. This became a turning point, when the Pope helped to focus world attention on the atrocities taking place. Amnesty International estimated that 200,000 had died by the end of the occupation - almost one-third of the population.

It wasn't until I met Noam Chomsky in 1985 that I became involved. A friend had referred me to an article of his on East Timor and when I contacted him, he told me he would be coming to Victoria, British Columbia, the very next week. I had no idea at the time what a high profile he had. I attended his lecture, met with him, and told him that I had these photographs. He immediately put me in touch with the human rights and solidarity networks working on behalf of East Timor. I started getting calls from people all over the world. They just went nuts. They had a real lack of images. So for about two years, it seemed that all I did was print up photographs for the movement.

Seeds and cement

I believe that without the worldwide networks advocating on its behalf, East Timor would not be free today. The East Timorese continued, determinedly, to resist throughout the occupation, but without outside support, Indonesia would have crushed them. The attention we drew, in a way, created a holding pattern - it prevented Indonesia from completely wiping out the East Timor population, which they would have gladly done. The international community was watching them.

Upon my return to East Timor after 26 years, I was very saddened, though not surprised, to see the awesome devastation that had taken place. The core of Dili, the capital city, was basically burned to the ground. It was filled with crumbled buildings, others charred with only the outside shell standing. The Indonesians had taken their revenge against the East Timorese for choosing independence. There was little economic advance, though this is not surprising, as the Indonesians did nothing to support development there. It was easier to get around, though, as the Indonesians had built tarmac roads for military purposes.

But the East Timorese are a very resourceful and self-reliant people. Although there are rice shortages, there is, and always has been, subsistence farming. Though working with inferior land that was almost destroyed by the Indonesians, the markets are full of vegetable, pigs and chickens. The people are motivated workers, enthusiastically rebuilding with seeds and cement.

Elaine Briere is a Vancouver-based photographer whose work appears frequently in The Tyee. These comments are adapted from an interview published on the web site of Between The Lines, publisher of East Timor: Testimony. ![]()

Read more: Photo Essays

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: