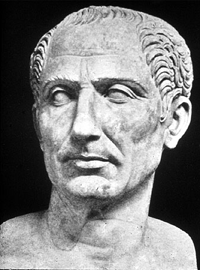

- Caesar: The Life of a Colossus

- Yale University Press (2006)

After more than 2000 years, he haunts us still.

Caius Julius Caesar, the epileptic son of an undistinguished patrician family, shook Europe to its core and shaped humanity’s future for at least two millennia.

Great generals, including Napoleon, have studied his campaigns like awestruck schoolboys. He was a brilliant writer who -- while fighting the Gauls -- dashed off a book on writing clear, plain Latin.

He understood male psychology so well that his legionaries begged to risk their lives for him. No later womanizer, whether Casanova or John F. Kennedy, could compare with his adulterous conquests. He could be brutal in the service of his policies, but also conciliatory. Julius Caesar saved Rome from itself, and paid with his life for it.

Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar: The Life of a Colossus is a superb modern biography of a man most us know only as a Shakespearean villain/victim. This is a shame, because Caesar’s life is remarkably well documented.

We don’t have much of his own writing apart from the Commentaries (I wish his book on clear style had survived). But Rome’s chattering classes wrote endlessly about him, and historians like Plutarch drew on sources now lost. Goldsworthy draws on all these sources to create both a vivid biography and a study of a society reborn from its own collapse.

Justice to the biggest briber

We now sentimentalize the Republic, but in Goldsworthy’s book it looks more like a gigantic racket. Rome was a rigidly stratified society in which everyone tried to link to someone richer and more powerful. The Romans passed lots of laws, but justice went to the biggest briber. For the aristocrats at the top, politics was both a game and the only way to secure a safe position for oneself and one’s family.

It was a brutal competition, often mixed with class warfare. The Republic had been convulsed for decades by civil strife and violent conspiracies: the whole racket had nearly collapsed when a gladiator named Spartacus led a revolt that turned into the Slave War. Each upheaval seemed to require yet another great leader and yet more erosion of the corrupt and incompetent Senate.

Caesar came from a little-known aristocratic family, but he followed a traditional career path: watch your father in his senatorial duties, make connections, do a little military service, make connections, bribe your way to various elected positions, make connections.

Like other ambitious young Romans, Caesar ran up huge debts. But he was able to spend other people’s money to become a consul -- one of the two men annually elected to run the country. Departing consuls would then be assigned a province of the growing empire. There, armed with imperium, the power of military command, they could rob the locals, pay off their debts, and return to Rome to continue the game.

A brilliant game-player

Caesar played the game brilliantly. Assigned to the provinces of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul, he responded to Gaulish and German raids by raising new legions -- a kind of private army. He then launched a campaign that extended the Roman Empire all the way to the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel. (He even managed a couple of forays into Britain, which were great PR for him.)

In the process, Caesar killed or enslaved over a million people, Gauls and Germans who were no barbarians. They just didn’t have the disciplined military culture that the Romans had developed over the previous few centuries.

Having brought Gaul under Roman control, Caesar wanted to go home and become a consul again. Consuls were immune from prosecution, and he knew his enemies would haul him into court as soon as he paid off his armies and returned to the city.

But no man could be consul twice within ten years, so Caesar had to break the law: he crossed the Rubicon River with his legions, bringing them into the Roman heartland, and that triggered a civil war. Having fought Gauls, Germans, and Britons, Caesar now fought Romans in Greece, Spain, and North Africa.

For a modern comparison, imagine General Douglas MacArthur returning from Japan, overthrowing Truman, defeating Eisenhower and Patton in a worldwide conflict, and then becoming America’s President for Life.

Now imagine MacArthur doing a very good job of running the U.S.: providing benefits for World War II veterans, promoting civil rights for blacks, and making the country stable and secure while helping the supporters of Ike and Patton. How many Americans would have objected to MacArthur’s demolition of Congress and the Supreme Court?

Not many, and not many Romans objected to Caesar’s disregard for Roman law and tradition. Even his enemies admitted that Caesar was doing the right things -- but in the wrong way. He might decline the “kingly crown” that Mark Antony offered him, but Julius Caesar had made himself a monarch.

Killing the saviour

A few conspirators decided to restore the Republic by killing its saviour. With Caesar gone, they thought that the Senate would regain its power and the old aristocratic game of connections and warfare would continue.

Goldsworthy’s description of the assassination and its aftermath is spellbinding and surprising. We expect assassins to be suicidal fanatics, not senior politicians and friends of the victim. So it’s startling to see that Rome did not at once clap Brutus, Cassius and the other conspirators into jail. Instead, the people listened to the assassins’ case, chose sides, and embarked on yet another civil war.

Octavian, Caesar’s nephew and adopted son, was a far less forgiving leader. He massacred the conspirators’ supporters, camouflaged his monarchical role, and as Augustus Caesar founded a dynasty that ruled Rome for centuries.

Carrying Caesar’s DNA

Ever since, governments around the world have carried the political DNA of Julius Caesar and his nephew.

Even after the empire’s fall, its successors wrapped themselves in its raiment: the Germans called their monarch the kaiser, and the Russians lived under a tsar. Ambitious nobodies like Napoleone Buonaparte studied Caesar’s career to follow his trajectory without making his mistakes.

Caesar’s lesson has never been to avoid stealing your country. His lesson has been to steal your country more carefully than he did, more carefully than Napoleon and Mussolini and Nixon did. But he framed political thought for two thousand years. Whether we approve or not, we still think and act in terms of republic and empire, warlords and dynasties.

Caius Julius Caesar was as close to a superman as humanity has ever produced. But even he could not transcend his own political culture. He could only push it to its logical extremes, without ever asking: Does it have to be this way? Do we have to kill a million people and destroy their societies just so we can go on playing this stupid game in Rome?

Only those who ask such questions will escape the fate of Julius Caesar and his descendants.