[Editor's note: Read part one of this article here.]

I've been a born-again carnivore since moving north from the city. Tofu doesn't grow on trees around here in Haida Gwaii, you know. But the slaughter -- well, I was there when we did in our chickens. I pulled the feathers from their skin. I skipped the turkeys; I can't remember how I got away with that. Lately we've been buying lamb, cut up and wrapped, from a farmer down the road. Oh fine, and a few steaks on Styrofoam from the grocery.

During my vegetarian days, I wasn't prepared to eat something I couldn't take responsibility for killing. Carrots I could pull, but slaughtering a cow? If you aren't going to build furniture, maybe you should sit on the floor, commented my meat-eating man. He had a point.

Barry chooses Harriet. She's the biggest and most ornery. It's time for her to go. Lenny, Team Pig's trapper, brings his .22 rifle at dawn. I wish I hadn't watched, but I did and that's all there is to it. I wasn't prepared for how long it takes a pig to stop moving when it dies.

Party preparation continues. Tom goes over on Thursday night to help attach the carcass to the spit, but the pig has been hanging for days and its back is twisted and bent. Drills and bolts come out. Things are done to its spine that don't seem right.

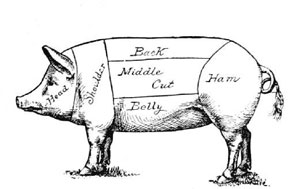

Problem number two: the rotisserie's maximum capacity is 130 pounds. Dead weight of the pig: 185 pounds without head. (And we thought they'd be 150 in September -- ha!) Off come the legs.

Barry and his friend Kim, who's come up from Vancouver, decide to start the coals at 3:30 a.m. on the day of the party. At 4 a.m., Wayne, who's building Barry's new barn, shows up, and by 5 a.m. they've almost lost the pig to the flames. Wayne builds a damper to cover the fire and Barry stands by with the hose. By 8:30 a.m., when we arrive, the pig skin is not as charred as Tom had feared. On the other hand, the inside is still cold.

Ruth has made muffins, bless her. We've brought an espresso pot for the stove. The fire burns, the pig rotates, but each turn tears the flesh from the bone. Tom dampens the fire and the drill comes out, then the butcher string, then the chicken wire. Finally, rebar stabilizes the carcass through each spin.

By noon, the day's heat is stifling and the inside of the pig is still cold. Tom begins to wonder how many ovens we'll need to cook the pig in pieces. But he's stubborn and perseveres. Sally, a friend who's come from the Yukon to visit relatives and help out with the feast, begins a side fire and Tom manages the heat, meat thermometer in hand. Coals here, coals there. A minimum temperature of 250 degrees on the skin. The pig continues to sashay around the rotisserie, but Tom slows the pace and cranks by hand every 15 minutes instead.

I escape to bake cornbread, get beer, buy chips. By 3 p.m. only he and Sally are left in the smoke.

Pigging out

A cross-section of islanders -- rippies and ruppies (our terms for redneck hippies and redneck yuppies) -- are invited to the feast. Cabin-dwelling government workers, Haida loggers, sunburned teachers, well-known artists, retired fishermen, young moms, the Hydro guy. The guests sit in a circle, as if there were a fire -- but stay well away from the smoky rotisserie. Everyone brings something -- strawberry shortcake, spicy green chimichurri, a big pot of beans -- but the beast has stolen the show. It crackles after hours on the fire. Two men lift the rod off, and within minutes a makeshift plywood table is covered in a greasy feast. The ravenous descend, picking through slabs of delicious pork roast for the even-more-scrumptious tenderloin.

The wannabe roasters deal with the bones, snapping the ribs off the carcass and putting them back over the coals. Tom, his T-shirt stretched with sweat, greasy handprints splayed on the back of his shorts, is done. A blues band plays as the sun goes down and the beer keg keeps pumping. By the end of the night, Ruth is the only one able to get up on the stage. She sings a song of thanks to our friends.

We take the islands' only limousine home with our neighbours Jen and Frank, sneaking Frida into the back. The limo driver slides open the window that divides him from us. "Next time, only humans." We pick her hairs off the carpet, the shelves of champagne flutes, the mirrors. Sure, we say. Frank hates dogs, but gets distracted and forgets by the time we get out several kilometres away. "Nice pigging with you," he says.

The slaughter

In September, we shoot the remaining pigs. Each time one goes down, the guys bleed it and hang it high off the bucket of the backhoe. The big machine trundles them across the yard to the trough of boiling water and the makeshift butcher table, where the rest of us scrape skin.

I can't touch myself after doing this job all morning -- not without thinking how much their flesh feels like my own. How the little pin hairs on my legs could use singing off with a butane torch, too.

Once the carcasses are smooth, Lenny takes over. He uses his father's knife to split bellies, spill guts and reveal thick slabs that will soon become bacon. Gary carts blue totes filled with viscera to the ocean-view road and tips them over the steep bank, the unofficial dumping spot for unwanted animal bits of all kinds. Tom's saved the kidneys and livers, but is crestfallen, later, when he finds a recipe requiring the discarded lungs. The eagles and ravens will feast, we say.

But Lenny has lost his heirloom blade. Could the lovely curved knife have fallen in with the guts? Yes, it's possible. Gary goes to look, comes back and says no. I walk out into the gushing rain with a hunch. It doesn't hurt that it takes me away from the scene of the slaughter for a bit, although where I'm going isn't much better.

Water courses over the riprap covered with twisted intestines slumping down the hill. I scramble down and pick through gall bladders and frothy pink lungs. I look out over the blue-grey ocean and remember the story of the killer whale found dead on the beach north of Tlell. During the autopsy, the scientists found pig remains in the belly. How did an orca eat a pig? Then I see a gleam under a grey sausage of innards, and I walk back with the precious knife.

Lenny is ecstatic. Gary is surprised. "Were you looking like a man?" I tease. He blushes and the women laugh.

Pig products

My rusty old fridge sat on my back porch for five years, and now I regret shipping it away. BC Hydro paid me $50 for it in the spring, but I want it back because I find Internet instructions for turning it into a temperature-controlled home-curing facility -- think salty pancetta and dry-aged chorizo.

Instead, the salted jowls hang from the ceiling of my basement on strings. The heads once dangled there too, but Tom finally dealt with those. He plans to make headcheese. Zero chance of me helping, I say, but I have to listen to him sawing pig skulls in half one night while I huddle in the living room.

"They have brains the size of golf balls," was all he said when he was done. The next morning he ran to the window.

"They're gone," he said.

He'd left the pig noses on the deck. Each one of the pink snouts had been whisked away by unknown scavengers -- maybe rats, maybe raccoons.

We invite our vegetarian friends Tyler and Hilary for dinner. We will still cater to our celiac friend, but it's hard to find a meatless meal in our house now -- too many pork chops in the freezer to get through. Excessive amounts of home-smoked bacon. Jellied pigs' feet anyone? Tyler grew up on a farm. He's been caving. Before the pigs, it was seafood. Oysters, baked until barely opened, fresh from the local farm. Scallops too. He loved the Telkwa lamb roast and Dexter beef stew.

Hilary, who's from Toronto, is a harder sell. Locally raised pig, we say, waving our cured jowls (in Rome they call it guanciale) in the air. Those eggplants come from far away. Have you seen any lentil farms on the islands? One could stick to hunting and gathering, of course -- berries cluster on bushes, salmon abound in the ocean, introduced deer need culling anyway. A Haida friend wonders how anyone finds time to garden when there is so much available outdoors as it is. Seaweed varieties, edible plants, clams. So much food.

But there is something about a nice piece of pork. As the platter of spaghetti carbonara passes, I catch Hilary's nose twitching. She'll relent, I know it. The value of eating locally is not lost on her. They've even been talking about going hunting with friends. Think of the driving you'll have to do, I say. Those deer, you can't shoot them off the highway. You've got to go way up the backroads. Maybe you'll find one. Maybe you won't. But a pig in a pen -- it's a sure thing.

I'm still working on her. Hell, I'm still working on my own commitment to the project for next season. A hog of one's own is a lot of meat. And if everyone gets in on the game, who'll want to come over to eat?

Tags: Food ![]()

Read more: Food