Looking for something to help deal with insomnia? Depression? Psoriasis?

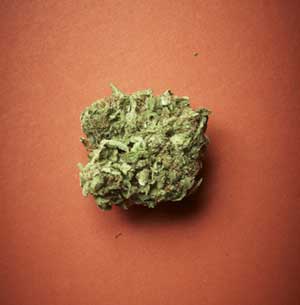

There's an app for that. It's called Leafly: a website offering a database of medical marijuana dispensary and delivery services, as well as crowd-sourced reviews of different strains of marijuana that help with any number of health ailments.

Leafly was the first acquisition of Privateers Holdings Inc, a private equity firm that formed in 2011 to get a piece of the burgeoning medical cannabis sector in the United States, worth an estimated $1.5 billion and growing.

Now, the firm is looking to Canada.

Since the federal government announced new regulations in June to open the market up to large-scale, commercial production of medical marijuana, Privateers partner Christian Groh says he's been watching Canada closely.

While Groh says his firm is still evaluating investment opportunities north of the border, "no matter what happens, we like the new system."

"We think it's fantastic," he says. "It makes a lot of sense from a business perspective."

Regulations signify 'profound change': producer

It also makes a lot of sense to Eric Nash, co-owner of Island Harvest in Duncan, B.C. His is one of the 171 businesses that have applied to become licensed producers under Health Canada's new regulations.

(Two have been granted so far, to Saskatchewan-based Prairie Plant Systems and its subsidiary CanniMed Ltd.)

For the past 12 years, Island Harvest has grown and distributed medical cannabis under Health Canada's old regulations. These allowed licensed medical cannabis users to grow up to 25 plants (and 150 grams of marijuana) for themselves, or to buy it from small-scale, designated producers.

Financially, the model was limiting. As a designated producer, Island Harvest was only allowed to grow for up to two patients at a time. Nash and his partner Wendy Little made their business work by cultivating expertise in the medical cannabis sphere: they did consulting, taught courses, wrote a book and generated expert witnesses for legal cases concerning medical marijuana.

Under the new regulations, producers have no limits on the number of clients they can serve or the amount they can produce, provided they can meet security requirements, which become more stringent as volume of production increases.

"That's a profound change in terms of initiating a commercial industry in Canada," Nash says.

He adds his business has been flooded with emails over the past three months from people interested in investing in Island Harvest, or looking for advice on starting their own operation.

"Software companies in the States, the oil industry in Alberta, the tobacco industry in the States, doctors, pain clinics all across North America... we've been contacted by numerous business people wanting to find out more," he says.

A less compassionate model?

Not everyone is happy about the commercialization of medical cannabis. The new regulations mean that users will no longer be allowed to grow their own. This system of small, home-based grow-ops was criticized by federal Health Minister Rona Ambrose for being unsafe due to fire risks, and more prone to abuse by criminal interests.

But it's cheap to grow at home, and some patients argue that taking away that right in favour of market forces will drive up the price, making an important medicine out-of-reach for some.

What's more, the new regulations have no place for dispensaries or compassion clubs. Under the new model, patients will buy directly from the manufacturer.

Although storefront dispensaries and compassion clubs have never been technically legal (many remain in operation but are frequently raided), they serve an important guiding purpose for medical marijuana users, says Philippe Lucas, a PhD student in the University of Victoria's Social Dimensions of Health program.

Lucas, a former Victoria city councillor who founded the Vancouver Island Compassion Society, has researched the impact of dispensaries on the patient population as part of his academic work.

"Dispensaries offer important face-to-face contact and can help give patients a solid sense of the safest and most effective strains," he says. "The new program will not allow community-based access."

With some doctors feeling unprepared to offer expert advice on the subject, patients will have to navigate options on their own -- hence, services like Leafly.

While Lucas does see advantages to patients under the new system ("large-scale licensed producers is probably the quickest path to getting the provinces to cover the costs," he says), he laments the lack of patient-centred care in the new regulations, in particular the fact that dispensaries are left out.

Primed for growth

Although large-scale producers can't market to the near half-million customers expected under the new program, other companies can brand and market certain strains, and then refer clients to the producers that make them.

Olympic gold-medalist Ross Rebagliati recently announced plans to produce a Ross's Gold brand of medical marijuana. The snowboarding champ almost had his medal stripped away after testing positive for pot in the 1998 Nagano Olympic Games.

Patrick Smyth of Ocean Eclipse Capital Advisors is one of Rebagliati's partners. Smyth says he typically works in the high-tech sphere, but became interested in medical marijuana after a mutual friend introduced him to Rebagliati at a function in Whistler in January.

Since then, Smyth has been contacted by other producers looking for investors. In Vancouver's venture capital sphere, he says, "there's a lot of talk, a lot of people looking at it... but I don't think the industry's mature yet."

Still, he says, "the feeling I get is that this has big potential as an industry." ![]()

Read more: Health, Local Economy, Federal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: