People have always disagreed about climate change. But for two fleeting years starting in 2006, it really seemed like most North Americans had accepted the climate narrative pushed into the mainstream by Al Gore and Lord Nicholas Stern: that in global warming humankind faced its greatest ever challenge, but solving it would make us all richer and stronger.

That worldview was so compelling, you may recall, that it won Gore the Nobel Peace Prize and elevated environmental worries to the top of North America's political agenda. It also caused Canada's Conservative Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, to assert in 2007 that global warming is "perhaps the biggest threat to confront the future of humanity today." Well, we all know what happened next.

Wall Street collapsed. So did climate talks in Copenhagen. Americans elected a Congress more polarized than any other in U.S. history. Cap-and-trade legislation fell to pieces. Activists declared war on Canada's oil sands. Harper's government declared war on activists. Media mostly ignored a global boom in climate-saving technology. And humankind's carbon emissions continued their inexorable rise.

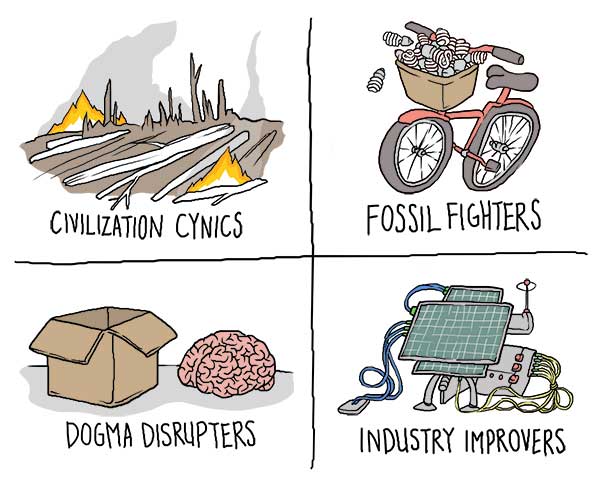

It now seems improbable that a single, compelling climate narrative could recreate the environmental zeitgeist of 2006 and 2007. Instead, four influential subcultures have risen in the intervening years, each with its own story to tell about the limits and opportunities of a warming planet. Taken together, they represent the fears and hopes of a generation living through tumultuous global change.

The Civilization Cynics

Imagine waking up one day suddenly unconvinced by western society's founding myths. You realize human progress is a sham. Endless growth, impossible. Your middle-class lifestyle? Built atop a battery of horrors: factory farming, rainforest destruction, mass extinctions and a dangerously warming climate. How would your world look if you admitted civilization is teetering on collapse?

"The funny thing is, as soon as you say it's not going to be all OK, that's a huge weight off your shoulders," Paul Kingsnorth, a widely published U.K. writer and former environmental campaigner, told The Tyee. "It allows you to be way more honest." That idea is central to the Dark Mountain Project, a network of writers and artists seeking new meaning in a civilization they're convinced is falling to pieces. Kingsnorth co-founded it in 2009.

"Lots of things are collapsing around us, but we still need to get on with our lives," Kingsnorth explained. Unconvinced the "green growth" promised by new clean technologies can save civilization, but dubious of an imminent "zombie apocalypse," Dark Mountain attempts to envision a humbled human existence more closely connected to nature. "We're not looking for a program to save the world," he said.

Kingsnorth spent much of his earlier career as a green activist trying to do just that. Over time he grew dismayed with the movement. "A lot of greens are not being honest about the causes of environmental destruction," he said. Oil firms like Shell are indeed ruining the planet, he agrees. But so are the regular people who buy their products. "We've seen the enemy and it's us," Kingsnorth said. "We're all complicit."

Since launching Dark Mountain in 2009, and publishing four anthologies of "Uncivilized" writing, Kingsnorth has watched the project grow into a "minor global movement," giving voice to fellow Civilization Cynics around the world. "We've tapped into a current," he said, "a sense of hopelessness and doom, and more interestingly than that, a positive desire to engage with what comes next."

The Fossil Fighters

For years you've felt an uneasy disconnect between your low-carbon lifestyle and the rising global temperatures it seems to have no impact on. Your home is lit by energy-efficient lightbulbs. You bike to work each morning. The produce in your fridge is organically grown and sourced from farms less than 100 miles away. What more can one person possibly do?

"Those things are all incredibly important," Phil Aroneanu, co-founder of 350.org, a leading opponent of the Keystone XL pipeline, said. "But they won't alone solve climate change."

Ultimate control over Earth's fate, he believes, resides in the corporate boardrooms of Shell, Exxon and other producers of fossil fuels. "We really need these companies to keep 80 per cent of the [oil, gas and coal] reserves they have in the ground," he said.

That won't happen without a fight. Ruining the planet makes those firms filthy rich. Since they can purchase political influence at the highest levels, the only recourse for regular people, Aroneanu is convinced, is to hit the streets en masse like the civil rights protesters of an earlier generation. "We need a huge societal shift," he said, "and only a social movement where everybody's involved" can achieve it.

Social movements require symbols. And few are more potent these days than the Keystone XL pipeline. The campaign by 350.org to defeat it could prevent a huge new source of carbon emissions. But Keystone, Aroneanu said, "is also a microcosm of what's wrong with our energy economy." It makes climate change feel real. "You can understand what it means to have a pipeline in your backyard," he said.

The same goes for tap-water lighting on fire. Tankers sailing through sacred rainforest. Boreal landscapes torn to shreds. Severed mountaintops. Oil-smothered ducks. These are the icons uniting Fossil Fighters across North America in battle. "We don't have the money to compete with the fossil fuel industry," Aroneanu said, "but we do have our creativity, our diversity and our bodies."

The Dogma Disrupters

At a family reunion you make the mistake of arguing with your conservative uncle about climate change. The whole thing is a hoax, he claims -- liberal junk science used to justify government intrusion into the lives of hardworking North Americans. Your uncle's an intelligent guy. Why does he think the 97 per cent of climate scientists who say the Earth is warming are wrong?

"On one level the debate is not really about climate change," Ted Nordhaus, co-founder of the Breakthrough Institute, a California-based environmental think-tank, told The Tyee. "It's about what society should look like." For years global warming has been conflated with tough controls on industry and big subsidies for clean energy. "Not surprisingly," he added, "a whole bunch of people on the right said, well, 'I don't think I believe your science.'"

Dismissing those people as idiots won't fix the situation. But changing the terms of the climate debate just might. Instead of hard limits on economic growth, think ultra-efficient buildings, widespread electric cars and power grids that resemble the Internet. "You get into very different mindset when you understand this as technological problem," Nordhaus said. "It's the politics of possibility."

That model sees government as the catalyst for a cleantech revolution, the same way federal policy helped create technology like the iPhone. It prioritizes coalition-building over conflict. "So much of the model on the left comes from the civil rights movement and protest politics," Nordhaus said. "You would think that's the only way social change has ever happened, and it's just not the case."

For now U.S. Republican denial of global warming shows little sign of changing. Same for the Canadian government's fixation on oil profits. But the answer for Dogma Disrupters isn't to hit the streets. They'd rather transform the assumptions that led us here. "What we're trying to do with climate change," Nordhaus said, "is force it out of the ideological frames that have defined the issue for a generation."

The Industry Improvers

You've just invented an incredible new product you're convinced will stop global warming. It promises to transform one of the world's dirtiest industries into the cleanest. But nobody in that dirty industry seems to care. You watch the eyes of executives glaze over as you talk carbon emissions and rising sea levels. Finally one of them asks you: "How will this new product save us money?"

"The adoption of clean products and services is being driven by economics," said Dallas Kachan, founder of Kachan & Co., an international cleantech consultancy based in Vancouver. Corporations, in other words, don't run on benevolent green ideals. They're interested in shrinking their ecological footprint if it makes them more profitable. "Saving the planet is kind of a pleasant after-effect," Kachan said.

Never has it been easier to do both at once. Kachan points to recent technology advances in sectors like clean energy, low-carbon transportation, water recycling, sustainable agriculture and green buildings. Cleantech, he explained, "is now built into more or less everything." In business parlance such innovations are referred to as "efficiencies." "It's not about carbon," he said. "It's about doing more with less."

Lately cleantech firms themselves have been forced to do more with less. Global clean energy investment peaked in 2011 at $302 billion, and has fallen steadily since. It's evidence of a maturing industry, Kachan believes, the same temporary slump faced by dot-com firms in the late 1990s. Politics are also a factor. "We've had completely underwhelming policy support for clean technology" in North America, he said.

Yet the "fundamental drivers" for cleantech remained unchanged: a world population set to hit 10 billion. Looming shortages of food, water and other vital resources. Rising global temperatures. Across the planet, Industry Improvers are looking for cheaper, better and less harmful ways to run human civilization. "The demand for clean products and services," Kachan said, "isn't going away anytime soon." ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: