[Editor’s note: This article runs in a new section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, sustainable economy we need from Alaska to California. Find out more about this project and its funders.]

Alicia Graham scoops sunshine batter into muffin tins on a bright Wednesday morning in Kamloops, B.C. The classically trained chef has a full day ahead of her in the commercial kitchen.

With the muffins baking in the oven, Graham turns her attention to chopping fresh produce. She prioritizes local ingredients, which, at this time of year, means honey, cabbage and beets from Kamloops and dried beans from Armstrong. The muffins in the oven contain the last of her carrot supply from nearby Thistle Farm for the season. She chops up some vegetables for soup, rinses lentils and gets out a pair of induction burners. Graham plugs them into retractable outlets that descend from the ceiling, placing them far apart from each other. Part of adjusting to a new kitchen, she says, is discovering how not to flip the breakers.

Graham began using the commercial kitchen earlier this year. It has enabled her to stop working for others and launch her own meal prep company, Pickle and Sprout. The entire 5,000-square-foot building is called the Stir and is part of a larger network of local food hubs in B.C. In addition to the kitchen, there are also offices for the staff of Kamloops Food Policy Council, which operates the space as one of its many initiatives to curb food insecurity in the community.

Kent Fawcett, the food hub’s manager in Kamloops, comes to the position with his own experience as a food entrepreneur. Through his former specialty — hummus — he learned that to properly scale a business like his, a factory or commercial kitchen is a must. Enter, the Stir.

Amid growing food insecurity in Canada, and the pervasive threat of supply chain disruptions due to the likes of global pandemics and climate change, the Stir is helping create a more vibrant local food economy and a greater sense of food sovereignty. At the same time, it’s reducing barriers for local entrepreneurs wanting to cut their teeth in the culinary business scene.

Today, the Stir counts nearly 30 businesses among its users. They each rent storage and time in the commercial kitchen. KFPC, the oldest independent food policy council in Canada, opened the facility in 2022 following a successful pilot project with a partner organization that also houses a commercial kitchen. They received $750,000 from the B.C. government as part of a provincial initiative to increase the number of local food hubs.

These food hubs are meant to offer a one-stop shop for helping launch businesses with objectives like catering, meal prep, selling at farmers markets or selling in grocery stores. They can also help farmers increase their profits by transforming raw products into something else. An apple could become a shelf-stable bag of apple chips; berries might become jam; cucumbers could be made into pickles.

The key to starting a culinary business, says Fawcett, is plenty of planning. Selling food comes with a strict set of regulations. It’s important to know if you’re planning on being in a retail environment because the rules get sterner, and you must strongly consider packaging. Or perhaps you’re planning to sell at the farmers market.

Take a cinnamon bun, for example. By itself, it’s a low-risk product that you’re allowed to make in a home kitchen. But if you want to add cream cheese icing? Well, now it’s high-risk and needs a commercial kitchen. Among the benefits of becoming a Stir Maker (Fawcett’s name for those who use the facility) is the risk-free aspect of it.

“People can try it,” he says. “They don’t have a lease on a building for a year and they don’t have a $50,000 piece of equipment that they have to try selling at a loss.”

The Stir is one of the more recent food hubs to open in the province. Commissary Connect opened in Vancouver in 2019 as the original site for what the province is calling the BC Food Hub Network. Next up was Plenty & Grace in Surrey. The first food hub to open on Vancouver Island was the Dock+ in Port Alberni, designed primarily for commercial fishing operations to process their catches.

The Stir is now one of 10 food hubs in B.C., with more slated to open (the Cowichan Valley, Kootenay Boundary region, Richmond and the Okanagan are all scheduled to launch food hubs.)

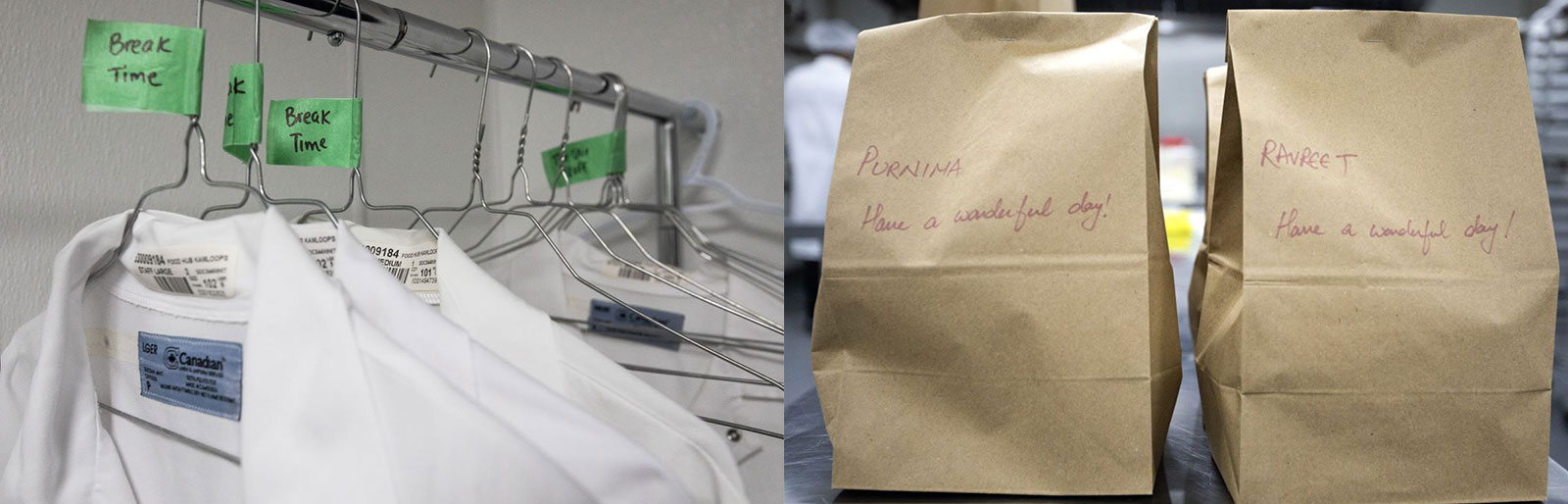

Back in the kitchen, a phone beeps from a table near Graham’s station. She’s sharing the kitchen today with Break Time, a virtual kitchen serving up Indian street food; they’ve got another order.

Break Time is also new to the space, after launching in January. Owner Arunima Sangwan noticed a market in Kamloops for homestyle Indian meals and Indian street food, and now offers extended hours of service to fill in gaps in the community. The new business has become quite popular with Indian international students craving a taste of home, and Sangwan has already hired four employees. She cooks up a lot of her mother’s recipes and never repeats a curry during the week.

Nearing lunchtime in the Stir kitchen, both Graham and Break Time get busy. They’ve split the wheeled stainless steel tables in the kitchen between them. While Graham uses the oven, Break Time’s Parveen Sharma oversees roti on a separate gas oven. The flatbread puffs as it meets the flames.

“Not every kitchen is really shareable,” Graham says as she continues prepping the day’s meals on the other side of the kitchen. How much space you get to use and its available hours are important factors. Stir Makers get 24-7 access to the facility and use an online system to reserve space. Hourly pricing varies from $16 to $26. Makers also pay for storage and must have their own commercial insurance, which can cost around $1,000 annually.

In addition to the usual suspects in a commercial kitchen (blast chiller, vacuum sealer, ovens, griddle and gas stove) there’s also a machine that makes filling jars and bottles easy. There’s pH testing equipment, a walk-in fridge and freezer, additional cold storage and even a pair of industrial dehydrators that look like personal spaceships.

The Stir helps take some of the mystique out of operating a successful culinary business. The path to success won’t be the same for everyone, but there are some common hurdles.

“We provide a community of support for food entrepreneurs because a lot of them are struggling in the dark by themselves,” says Fawcett. “They’re trying to solve all the same problems at the same time by themselves and really don’t know where they’re going.”

The Stir employees’ work as cheerleaders for the Makers never ends. In between meetings, they’re disinfecting the space, soliciting tips for picking out the perfect spatula — not too soft — and fixing doors. Fawcett says most of the initial cash they received went towards renovating the building. They’ve relied on a lot of grants, as well as sweat equity from staff. They were able to pick up an oven on a crazy good deal, and staff spent eight hours scrubbing it clean.

The program has been successful. Fawcett estimates between 40 and 50 jobs have been created thanks to the Stir. Kevin McHallam was one of the original members with his fermented drinks business KMK Living Inc., which makes products like kombucha and water kefir. He was able to move his business from home brew into the partner kitchen, and then into its very own space. McHallam credits his success to being able to access a kitchen like the Stir, which lowered his business’s risk.

“[The Stir] provided us with low-cost access to a health-authority-approved commercial kitchen that not only fit within our budget, but also our irregular processing schedule,” he says. “We were able to bring our products to markets, to test our product demand and then give us the data to prove our concept prior to opening our own facility.”

The kitchen hasn’t been too busy lately. Graham is in a few times a week for long days as she works on her meal prep offerings at Pickle and Sprout. Facility use fluctuates as need dictates, says Fawcett. For example, they have some seasonal Makers who use the kitchen only when farmers markets are open. There are still plans in the works for a storefront that features local products primarily made at the Stir. And they’re also looking into becoming licensed for meat processing.

The facility is helping community members live their culinary dreams. Sangwan was working at McDonald’s prior to starting Break Time. Now, she gets to share food with Kamloops that would make her own mother happy. As it nears 2 p.m., Sangwan and Sharma assemble their shift’s batch of meals. The food is packaged in paper bags with the deliverees’ names and “Have a wonderful day!” written in cursive.

Just a few months in, Break Time is ready to graduate from the Stir. Sangwan’s plan is to move just a few blocks away into a stall at the Yew Street Food Hall, where they’ll offer a full menu for dine-in, pickup and delivery. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: