[Editor's note: Every day this week we're featuring reports from Christopher Pollon's quest to follow a pound of B.C. copper from cradle to grave -- and back again. The story begins below in Princeton, B.C. To get a sense of the scope of the project, see this interactive map and introductory story.]

PRINCETON B.C. -- The "cradle" of this copper story lies here, about 300 kilometres east of Vancouver near Princeton, B.C., a boom-and-bust mining and logging town that by the late 20th century seemed used up and ready to die.

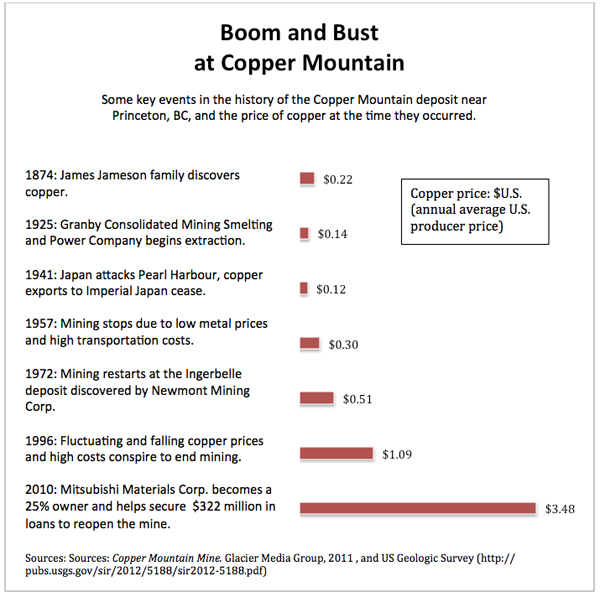

Between 1927 and 1996, some US$6-billion worth of copper had been dug from the mountains south of town, extracted by at least five corporations, now all long gone. What was left, most traditional assays concluded, wasn't worth the cost of pulling out of the ground.

But by 2011, change was on the horizon, driven by both new technologies and distant market forces 9,000 km to the east (see sidebar). Under new management, Copper Mountain again began producing raw copper for export, putting 380 people to work full time, and supporting about 1,500 other jobs indirectly.

"I've died and gone to mining heaven," Princeton town councillor Frank Armitage gushed at the mine's official re-opening. A 40-year veteran of the industry, Armitage is now both Princeton's mayor and Copper Mountain's human resources manager.

This dual role says a lot about Princeton. There's little separation here between the mine and the community, because without copper there's not much of a community left.

Cash from Japan makes it work

The story of Copper Mountain's modern resurrection goes something like this: when the 2008 financial crisis struck, and other miners were ducking for cover, Jim O'Rourke was wheeling and dealing. An engineer educated at the University of British Columbia, O'Rourke is a B.C. mining legend and its unrivalled copper king. He had already retired from launching two other mines -- the Huckleberry and Gibraltar copper mines -- when he pulled together a team, bought the 18,000-hectare mine site near Princeton, and in 2006 began drilling exploratory rock cores with urgent speed.

Despite many technical advances in geology and technology, extracting rock samples from across a promising ore body remains the only real way to know what lies below. By the time O'Rourke had drilled and analyzed over 100,000 metres of cores, two years later, he was confident there was enough copper beneath the historic workings to sustain about two more decades of steady mining.

Then, the coup: Mitsubishi Materials Corporation (MMC), an affiliate of one of Japan's biggest manufacturers, agreed to buy a 25 per cent stake in the mine outright and to buy all its raw copper. Eventually, MMC even secured $322 million in loans from a consortium of Japanese banks to finance the new operations.

Japan and British Columbia have a long history together in the copper trade, dating back to before the Second World War. Today, Japan is our biggest customer for raw copper (followed by China and South Korea) according to Bruce Madu, a director of B.C.'s Ministry of Mines. In his words, Copper Mountain's relationship with MMC is "an ideal scenario." The Japanese company's investment provided both initial capital and a guaranteed ongoing customer for the revived mine, while leaving a majority of its stock in the hands of existing shareholders.

Gravy days gone by

One day last August, I joined Rod Shier, Copper Mountain's chief financial officer, and three young mining analysts from Toronto and Montreal, in an SUV, to drive up from Vancouver to the site of so much renewed interest. The visiting analysts were friendly and personable, but the mood was far from upbeat: the gravy days of the most recent commodity boom were clearly over, they said. The value of gold -- much smaller amounts of which the mine also produces -- had plunged nearly 40 per cent from its mid-2011 high of over $1,900 (USD) an ounce. Copper was still at historic highs on this day, but the air was beginning to go out of its price too. (By March 2014, it would plunge below U.S. $3/pound.)

Earlier in the year, Toronto's Barrick Gold, the world's biggest gold miner, had written off close to $13 billion in losses, postponed spending, and slashed jobs and dividends.

As investor confidence in the mining sector has waned, cash for mine construction and new exploration has evaporated -- and with it demand for mining shares. Uncertainty hung in the air, as the stock analysts riding along chatted about mutual friends being "downsized" into unemployment.

"We need a splashy find to create some retail fizz," offered one analyst, a statement that roughly translates as: 'We need some good news to convince investors to trust mining stocks again.'

Later in the day good news was all around us as we drove up Bridge street in Princeton, a town of just under 3,000 people 20 km north of the mine. "Now you see mothers walking down the street with baby carriages," Shier -- one of the key executives who joined O'Rourke early-on to make the mine a reality -- pointed out proudly.

A 21st century mine

A pioneer prospector of the B.C. Interior might not recognize Copper Mountain as a mine at all. Here a landscape is being consumed by giant machines that lose their scale against the five-km-wide mine site. Komatsu trucks, the size of small houses, carry 220-tonne loads of ore from open pits to the surface. Rough boulders of rock are broken up and carried on a conveyor belt to a mill. There the ore is broken into progressively smaller pieces, and mixed with water and chemicals ("reagents") to separate the copper, and minute quantities of gold and silver, from the tailings that will be left over. The mine's final product, the commodity its sells to the world, is a fine powder containing about 30 per cent copper with tinier amounts of precious metals.

The mill is as loud as Niagara Falls, and barring a few men monitoring computer screens in a Spartan office, almost a ghost operation. Many of the direct jobs at Copper Mountain are to serve the technology at work 24/7, including the machines that do the heavy lifting.

The eastern analysts have arrived with serious questions about the mine's ability to make money. They are here to confirm Copper Mountain's estimates of future production; what they see will decide whether they advise their clients to sell, hold, or buy the company's stock.

To that end they are fixated on two things: the rate at which the company is removing copper from the ground, and what it is costing to do it. Rod Shier assures them that recent capacity problems with the mill are being addressed; within days Shier will travel to Japan to pitch Mitsubishi on the need for $30 million-plus for improvements. An engineer adds that the goal is to "drive tonnage as high as we can." The analysts seem satisfied that the mine is on solid footing.

"At the end of the day the name of the game is profitability," analyst Stefan Ioannou of Haywood Securities tells me later. "You can produce a gazillion pounds of copper, but if it's costing you six dollars a pound [hypothetically] to produce, and you're selling it for three, you don't need to be a rocket scientist to know it's not a good business model."

BC: we're 'price takers'

It's all very cordial, except for a single sour note near the end of the day when I pose what I think is an innocuous question: How much say does Mitsubishi Materials have in day-to-day decisions at Copper Mountain?

Shier is incensed. He jabs a finger at the other executives in the room and asserts that they run the mine day-to-day -- "end of story."

The significance of the moment resonated over the following weeks, as I tracked B.C.'s copper from Princeton, across Asia, and back again. The engineers and geologists in that room may call the shots about separating copper from mountains of ore, but when it comes to why the copper is leaving the ground at all, the real levers are being pulled somewhere else.

British Columbia is endowed with enviable deposits of copper, coal, gold and natural gas. Yet I'm about to learn that without the demand, financial partnerships and technological expertise provided by Asian players, most of our valuable commodities would stay in the ground.

Canadians may be miners to the world, but we do not control our own destiny: we are price takers, at the mercy of shifting forces that will increasingly determine how, when, and for how much money, our resources will be taken. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: