[Editor’s note: In today's economy, packaged or prepared "kid-ready" meals can be a tempting solution for stressed-out parents. But the results aren't good for Canadian kids, with the number of them struggling with obesity on the rise. In response, a loose alliance of educators, parents, farmers and doctors argue that it's time to go back, for some of us way back, to the way our forebears ate: fresh food, made from scratch, eaten together. In this series, Tyee Solutions Society reporter Katie Hyslop visits farms, schools, full-length mirrors and our own kitchen cupboards to examine how we lost our way when it comes to feeding our kids, and how we can get back on the path to wholesome, healthy eating.]

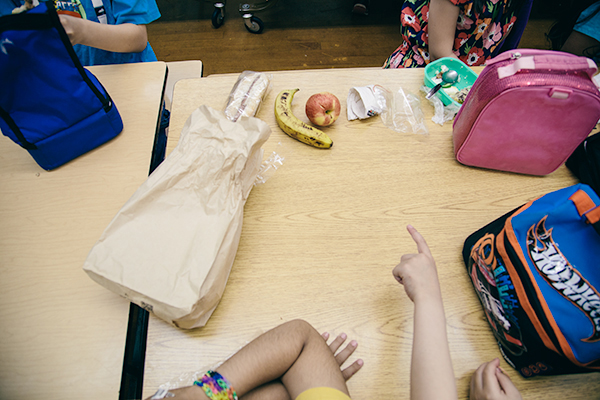

When you think of breakfast and lunch programs at public schools, it usually brings to mind kids and youth whose parents can't afford to keep their pantries stocked with enough food for three meals a day.

But when Amanda Sheedy talks about the need for a national food program in Canada, she's not as concerned about poor kids' food insecurity as she is about every child's. If they're bringing tater tots and white bread peanut butter and jam sandwiches from home for lunch, they have worse problems than depending on subsidized food.

Sheedy, program manager at Food Secure Canada, said in a phone interview that the country faces "a health crisis that has a lot to do with food. [Canadians] still haven't managed to come up with a comprehensive way to address the growing obesity crisis, and we think that school food programs are a great way to tackle it."

Childhood obesity rates are on the rise. Almost one-third of Canadian children are overweight or obese, as determined by Health Canada using the Body Mass Index, a somewhat controversial measure since using height and weight to calculate body fat can mistake healthy tissue as fat.

Nonetheless, it's a status quo that a coalition of health and food-related organizations including Food Secure Canada want to change. Their joint initiative, "Raising the Bar on Student Food Programs," is calling on Health Canada to set national school food guidelines, and more daringly, to fund school food programs.

Raising the Bar hasn't got an ideal food program in mind yet. But possibilities include a mid-day meal offered to all children that would cover at least three of the four food groups recognized by our national food guide.

Once the coalition has settled on the program design it feels would do the best job of getting healthy food to kids, it plans to submit a formal proposal to Health Canada to share in funding it.

As a variety of media organizations have noted, Canada is the only country in the G7 group of leading economies or the 34-nation Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) without a national school food program.

Instead, Ottawa has left school food policy strictly up to the provinces, which have responsibility for education under Canada's constitution. All have a school food policy of some kind, and five have provincially funded school food programs. Nunavut is working on a school food policy, and the Northwest Territories funds school food programs; only the Yukon to date has neither a policy nor a program (see sidebar).

British Columbia has had a provincial school food policy for nine years. Local districts have adopted a variety of food programs from universal hot lunches or breakfast -- where every child eats free -- to regular pay-to-eat cafeterias; a fresh fruit and veggie program that provides a free locally-produced snack to every student 13 times a year; or sometimes, nothing at all.

But Sheedy sees her coalition's goal as new. Most food programs of the past were aimed at food-insecure children, she said. "This is more of a health program, because it is very much about preventing a lot of the chronic diseases that we now see: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, some cancers that are very much diet-related. It's time for us to really educate our kids about what healthy eating means."

The ideal federal program needn't replace provincial ones that already exist, Sheedy makes clear. But it should provide enough additional funding and appropriate guidelines to ensure that all kids, regardless of their economic background or what's in their kitchen cupboards at home, have access to healthy food at school.

And the federal government has been prepared in the past to venture into health policy, another provincial responsibility. An article posted on Lions Bay Community News website quotes federal Health Minister Rona Ambrose as telling the West Vancouver Chamber of Commerce last March that "our government is committed to promoting healthy living and healthy weights, and preventing chronic disease for all Canadians."

It's not entirely clear how much a national school program would change that, even among kids. The United States has had a school meals program for over half a century. After managers notoriously tried to classify ketchup (and succeeded in classifying pickled relish) as a vegetable dish, the program has been undergoing an overhaul to improve the nutritional quality of what's served. And some studies have shown that even nutritionally suspect school food is better than no food at all for kids' health. Still, U.S. cafeterias continue to lean heavily to "kids foods" like carb and fat-drenched pizza and french fries, while obesity rates among Americans six to 11 years old have more than doubled since 1980, reaching 18 per cent in 2012.

Then there's France, praised earlier in this series for its healthy, varied and cooked-from-scratch school lunches. France doesn't have a national meal plan. It does have a national school food policy, but every school program is developed and subsidized by a municipal government.

It's too soon to know whether British Columbia's school food guidelines, mandatory for only six years, are having an impact on child obesity or related health problems. So, if we don't know whether our provincial school food policies are broken, do we really need a national one?

Holes in our food basket

Mary McKenna, a dietician and professor of kinesiology at the University of New Brunswick, has spent 20 years studying school food programs. But a patchwork of provincial programs and the challenge of funding her research have frustrated her goal, in collaboration with Raising the Bar, of compiling a first comprehensive list of every school food program in Canada.

Even so, McKenna's very familiar with the national school food landscape.

Those providers seem to favour school breakfast programs over lunch, for reasons McKenna conjectures are due to the plentiful research demonstrating that learning suffers when students are hungry. Breakfast is also the meal most likely skipped, though McKenna admits there's less research on how many kids skip lunch, or what effect that has on learning.

But why hasn't Health Canada or another federal department stepped in before now? In addition to Ottawa's historically selective toeing of the constitutional line, and the fact that the rise in obesity-related illnesses has only recently been identified as a national issue, policymakers have traditionally viewed food programs as a solution to hunger, not to poor nutrition. And hunger was supposed to be solved by social policies, most of which are also provincial responsibilities.

"The social safety net was supposed to be strong enough [through social assistance programs] that the families would be able to provide food for their kids, and then at the school they wouldn't know 'is this child buying lunch with money from social assistance? Or are this child's parents able to pay?'" McKenna explained.

But citing how many different programs are out there aimed at fighting hunger, McKenna said the evidence indicates the social safety net has failed kids facing poverty-related food insecurity, while it was never meant to catch kids who had money, but whose families or schools provided nutrient-poor food.

A program that includes every child can also help erase stigma, McKenna argues. "If it just becomes a program for the 'poor kids,' that's not ideal. Kids are smart, they know the score on that sort of thing, and we certainly don't want it to be stigmatizing."

Going beyond calories

When critics of national food programs cite the U.S. as an example of good food intentions gone bad, Food Secure Canada's Sheedy points out that our southern neighbours started their food program after the Second World War, out of concern over the diminutive stature of the American male.

"There weren't enough big men, ultimately, to fight the war," Sheedy said. "So they decided to put in place this program to make sure kids were receiving the basic nourishment they needed on a daily basis to grow and thrive. Very different from what we're seeing today." These days, she underscores, our "mal-consumption problem" is at least as big as our food insecurity problem.

Instead of tossing aside the idea of a national food program altogether, Sheedy said we need to rethink why we need one and how we could use it. Her priority: teaching kids to appreciate fresh, healthy food, versus filling their guts with anything to keep them growing.

Today, the American program provides subsidized food to over 31 million children year-round. But Congress must approve budget increases to cover rising food costs. That can be a slow process, leaving schools to improvise with canned or frozen fruits and vegetables instead of fresh; processed beef instead of chicken; or staff downsizing.

Nonetheless, each American school is expected to meet national nutrition standards. The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, passed in 2010, required that school meals align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the U.S. equivalent of Canada's Food Guide.

Two years later, the U.S. government made even bigger changes to school food policies when it introduced stricter food guidelines, including a calorie cap on meals. Foods like pizza had to be made from healthier ingredients like whole grain flour. Most trans-fats were banned. The level of sodium allowed in meals will decline over the next decade.

While menus may still not exactly be a nutritionist's dream, studies have shown that kids receiving subsidized school meals, even before the new guidelines, do see positive health results. These have included: a better diet than that of low-income peers who skipped school breakfast, or ate it elsewhere; a lower likelihood of eating junk food, and a greater one of consuming fruit, veggies or milk at school; and a lower BMI than those who skipped school meals (although this applied only for breakfast programs).

Raising the Bar isn't looking for a uniform, nationally-managed program. "We understand the program's not going to look the same up in Nunavut as it does in P.E.I.," Sheedy said. "As a matter of fact, we see that there's a great richness of programming happening across the country right now. [Our idea] would be very much to fund and support what's on the ground already, rather than replacing it with a standardized program."

She also sees a role for Ottawa in ensuring that national food guidelines -- which most if not all provincial programs already follow -- are met.

Not our responsibility: Health Canada

Raising the Bar would especially like to see a national program support a mid-morning school meal. That "has been shown to have the greatest impact for the money," according to Sheedy. "It manages to straddle the kids who show up at school without having eaten in the morning, along with the kids who may not have a healthy meal. It helps those kids get through the day." Portions needn't be large, but at least three food groups should be on the plate.

For now, Raising the Bar remains an idea-in-progress with one especially high hurdle to get past: persuading Ottawa to unlock the needed money. Funding just 20 per cent of program costs would cost Ottawa about $550 million a year, as the coalition Raising the Bar estimated in 2012 -- slightly less than four of the new F-35 fighter jets the government is still planning to buy.

Britain has budgeted 1 billion pounds (C$1.8 billion) for a universal school meals program for Grades 1 through 3 that began this September.

Sheedy's given the money question some thought, and has a healthy suggestion for how to raise some of it at least: a 10-cent per litre tax on soda pop. If you consider that Canadians consume 358 billion litres of soda annually, the $358 million in new tax revenue would cover more than half of what Raise the Bar is seeking.

That proposal might even have the added benefit of cutting down on Canadians' consumption of sugary drinks. Even so, and even before receiving Raising the Bar's formal submission, Minister Ambrose's department is giving it a thumbs-down.

"The provision of food in schools is a provincial and territorial responsibility," Eric Morrissette, senior media relations advisor for Health Canada, emailed to underscore. The federal government plays its part, his email added, by developing "healthy eating guidance," like the "Eating Well with Canada's Food Guide," which most provincial programs have adopted.

Changing the label

So what is Health Canada doing to counter child obesity? In 2010, the federal health minister, with every provincial counterpart except Quebec's, adopted a federal, provincial and territorial Framework for Action to Promote Healthy Weights. A 2013 progress report listed initiatives taken by all three orders of government to combat childhood obesity. But the "progress" referred to carrying out planned actions, not to any actual reduction in childhood obesity rates -- is unlikely in any case to have changed significantly in just three years.

Meanwhile, Health Canada put over $210 million in 2013-14 into the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program and Nutrition North Canada, mainly to tackle maternal, infant and child nutrition issues among indigenous citizens. Those services have been in desperate need of funding, but benefit only a small segment of the population.

In July, Ambrose also proposed a redesign of food nutrition labelling, intended to help prevent obesity.

Redesigned labels would group all the sugars, both added and natural, together in the ingredients list; put the least desirable nutritional information -- calories, sodium and added sugars -- at the top of the label to draw more attention; and streamline serving suggestions to make it easier to compare nutritional data of similar products.

But Sheedy said that such changes are small measures that haven't shown much success in preventing or reversing obesity in the past. "Without a comprehensive strategy, including protecting children from junk food marketing, [and a] school food program that also educates children and their parents about healthy food, we will not see any progress on obesity," she flatly predicted.

Neither scolding us for the food we eat nor throwing shame at fat people have stopped obesity and related illnesses like diabetes or heart disease from increasing among adults and kids in Canada. Nor have we made it easier for families to provide healthy food when wages are low, working hours are long, and there are cheaper, quicker and dirtier food options out there.

But schools can and do have some control over the day of kids who spend the majority of their waking hours in classrooms for eight months of the year. For the activists behind Raising the Bar, that's an opportunity to capture kids' tummies -- and hearts and minds -- instilling good dietary habits that will last to adulthood, and maybe even influence how they feed the next generation of children.

This Wednesday: Educators wage a veggie-roots campaign to put industrial agriculture in context, one school plot at a time. ![]()

Read more: Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: