Just one week after the Lax Kw'alaams band rejected a $1-billion offer by Petronas to build a liquefied natural gas terminal at the mouth of the Skeena River in British Columbia, Premier Christy Clark has signed an agreement with Malaysia's national oil company to "establish the path to a final investment decision on the project."

Part of that path includes a long-term commitment by the provincial government not to raise natural gas royalties, regardless of changes in global prices for the commodity.

Natural gas, like oil, is one of the world's most volatile commodities in price.

"With this certainty, industry can plan their operations over a longer period of time and commit capital to jobs and production needs, while the Province has a guaranteed royalty revenue each year," said a government news release.

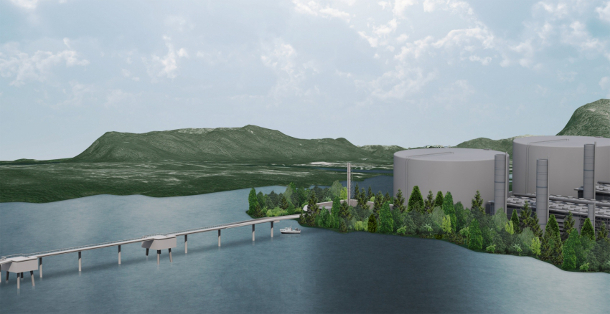

Pacific NorthWest LNG, which is largely owned by Petronas, has yet to make a final investment decision, and the proposed multibillion-dollar project near Prince Rupert must still pass an environmental review.

Just what kind of company is Petronas, and what's its relationship to the Malaysian government? The Tyee looked at the public record.

1. The government of Malaysia set up the national oil company in 1974 when oil prices jumped from $1.50 to $12. The government did so with the goal of safeguarding "the sovereign rights of Malaysia and the legitimate rights and interests of Malaysians in the ownership and development of petroleum resources." The company's success has helped the government to reach out to the Muslim world.

2. Over the following decade, the company expanded. It bought out Conoco's oil and gas concessions in the country, opened hundreds of gas stations, built its first refinery, and sent its first LNG shipment to Japan. By 1983, Malaysia oil had transformed the country, where the activities of Petronas provided 28 per cent of its revenue. In recent years, Petronas has accounted for as much as 40 per cent of the government's revenue.

3. In 2004, Malaysia's leadership realized that oil and gas production had peaked in the country and that hydrocarbon reserves could be exhausted within 30 years. As a consequence the firm expanded into 25 countries, including Myanmar, Vietnam, Iran, Chad and Sudan. In the process, the Malaysia International Shipping Corporation (MISC), a subsidiary of Petronas, became the world's largest single owner-operator of LNG vessels and the world's second largest owner-operator of Aframax oil tankers, a medium sized transport ship. In 2003, Petronas and Chevron/Texaco invested billions in Chad with the goal of making the country a model of stable and prosperous development. The money brought little but grief and chaos.

4. The management of Petronas is unique. It does not report to parliament, but to the prime minister of Malaysia. In 2013, a study by the Malaysian based Research for Social Advancement concluded this arrangement was problematic: "The fact that PETRONAS reports directly to the Prime Minister and parliament has absolutely no oversight of PETRONAS, not even to review its operations and financial accounts, was identified by several as a critical weakness in the system that is a huge challenge to transparency and accountability in the Malaysian [oil and gas] industry."

5. In recent years there has been increasing debate in Malaysia about the role of Petronas and a lack of government transparency and accountability on oil revenues. A number of oil-producing regions in the country, for example, do not feel they have received their fair share of royalties from offshore oil extraction.

6. In 2012, Petronas purchased Calgary-based Progress Energy for $5.5 billion. The company specializes in the hydraulic fracturing of unconventional resources in the Montney shale gas formation in northeast British Columbia and northwest Alberta. At first Ottawa rejected the takeover, saying it wasn't in Canada's best "net interest" for one foreign firm to mine unconventional gas, liquefy it, and then export the fractured gas to Asia through its own terminals and ships. But Ottawa later approved the deal. Shortly afterwards, Petronas sold a 15 per cent stake in Progress Energy to China Petrochemical Corporation (SINOPEC). To supply the proposed LNG terminal near Prince Rupert, the company will have to drill and fracture thousands of wells on the First National territories of Halfway River, Prophet River, West Moberly and Blueberry.

7. In 2012, the news service Reuters reported that Malaysia's prime ministers have treated Petronas "as a piggy bank for pet projects since it was established in 1974." The article added that "Unlike other oil-rich nations such as Saudi Arabia, Norway or Brazil, Malaysia runs chronic, large budget deficits that have expanded even as oil revenues increased. Last year's fiscal gap, at five percent of gross domestic product, trailed only India's for the dubious distinction of biggest in emerging Asia, and it may widen this year."

8. Malaysia scores poorly on most transparency and corruption indices. In 2011, for example, Berlin-based Transparency International reported that Malaysia scored, out of 28 nations, in the bottom half of its Bribe Payer's Survey. More than half of 3,000 executives from 30 different countries said they had lost a contract in Malaysia because a competitor paid a bribe. In 2013, two senior Petronas managers were charged with bribery. In 2015, Malaysia courts acquitted one executive, but convicted another for bribery and money laundering.

9. In 2014, the Oslo-based Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative invited Petronas to adopt its transparency standards so that Malaysian citizens can better gauge how well resource revenues are being spent and managed in the country. Opposition leaders endorsed the recommendation, but to no avail.

10. In 2014, Petronas chief executive Shamsul Abbas told The Financial Times that it would pull the plug on its $10-billion liquefied fractured gas project near Prince Rupert due to the creation of an LNG tax by the British Columbia government and a "lack of appropriate incentives." Shortly afterwards, the government of British Columbia lowered its proposed LNG tax from seven per cent to 3.5 per cent.

11. The global oil shock of 2014/2015 has had a dramatic effect on the Malaysian government. It recently axed energy subsidies. The political implications are also significant, according to Kai Ostwald, an assistant professor at the Institute of Asian Research and the Department of Political Science: "Malaysia's dominant Barisan Nasional government has long relied on revenue from the state oil company Petronas to dispense patronage and fund populist programs." ![]()

Read more: Energy, BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: