[Editor's note: This is second in a series of in-depth audio reports and text articles investigating the state of Vancouver drug policy 13 years after the ground breaking Four Pillars approach was adopted. The project is a partnership between The Tyee and the University of British Columbia's documentary radio series, The Terry Project on CiTR.]

On a day in June, just before end of the school year, drug and alcohol counsellor Heather Charlton roams the halls of Templeton Secondary School in East Vancouver, striking up conversations.

As two teens walk past, she invites them to an after-school BBQ. Sorry, they say, they are grounded by their parents and won't be coming. Charlton asks them how they will be spending their summer.

"Chillin'," they respond

"Chillin'? Chillin' like a villain? Are you going to get into trouble? Are you going to make healthy decisions?" she asks.

Charlton, who has been doing this work for over 16 years, has a bright streak of highlights through her hair, and she exchanges text messages with her students.

A group of teenage girls say Charlton is like an older sister to them.

"She's a very useful resource for this school, and really important," says one student. "I just wish she was here five days a week, because we like her so much and want her here all the time!"

Charlton serves both Templeton and Vancouver Technical secondary schools, meaning that over 2,500 students vie for her time.

In 2001, Vancouver's groundbreaking drug policy, A Framework For Action: A Four-Pillar Approach to Drug Problems in Vancouver, claimed that the city's drug prevention programs were ineffective and needed to be replaced. Today, those old programs are gone, but the new ones are underfunded and struggling to keep pace.

Trying to gauge whether the current pillar of prevention is seriously cutting into drug use among teens is difficult, because surveys of adolescent substance use typically cover the entire province, not merely Vancouver. But prevention specialists like Charlton clearly have their work cut out for them.

B.C. students drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, and use marijuana at higher rates than the national average, according to a 2012 survey by Health Canada.

You can hear the documentary radio instalments that accompany this series by clicking on the icon below. Or you can subscribe to the series on iTunes.

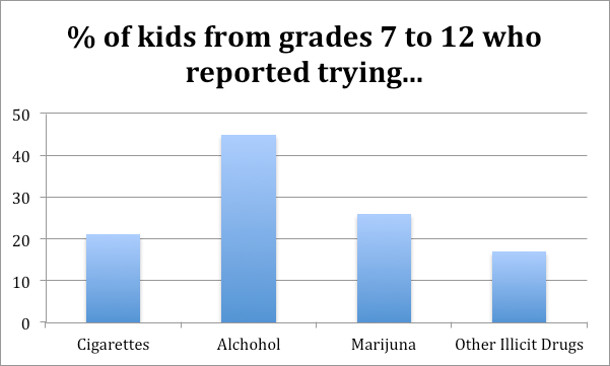

According to most recent figures provided by the 2013 B.C. Adolescent Health Survey, which included 30,000 secondary school students from all across the province, 26 per cent of respondents have used marijuana, 45 per cent drank alcohol, 21 per cent tried smoking, and 17 per cent used an illicit drug other than marijuana. Of that 17 per cent, prescription pills without a doctor's consent and hallucinogens (including MDMA) had the largest shares.

A 2006 report comparing Vancouver to the rest of the province found that less Vancouver students report using alcohol and marijuana, but they report similar rates of using other illicit drugs.

The percentage of B.C. students that report using illicit substances has slowly fallen since Vancouver passed its Four Pillars. However, prescription drug use without a doctor's consent remains high (nine per cent in 2003, 11 per cent in 2013), and drugs like MDMA have surged over brief periods.

Change in approach

In B.C. schools, drug prevention messages typically have been delivered by police officers seeking to scare students from using drugs.

One of the most popular prevention initiatives has been to screen the documentary film Through a Blue Lens. The film, which follows two police officers on their beat in the Downtown Eastside, features harrowing scenes of intravenous drug users. Produced in 1999 and seen in 22 countries, the film continues to be screened in some B.C. schools and community centres.

However, a growing academic consensus -- in disciplines as diverse as psychology, nursing, social work, and public health -- claims that these abstinence-only drug education initiatives, or 'just say no' approaches, are ineffective, if not counter-productive.

"The biggest myth is that if a young person is scared of something, they're not going to do it. We know that's wrong," says Michelle Fortin, executive director of WATARI, a drug counseling and support society.

Since The Four Pillars, Vancouver has moved beyond these approaches. DARE, a drug prevention program administered by RCMP officers, is no longer available in Vancouver schools.

At Templeton Secondary, Charlton approaches one young boy holding a skateboard. "Did you hear my announcement about skateboarding?" she asks. "SACY's summer programming is free! You can come every single day, and do cool stuff."

Charlton is a youth engagement worker with SACY, or the School Age Children and Youth Substance Use Prevention Initiative. SACY is administered by the Vancouver School Board and Vancouver Coastal Health.

Charlton goes to students where they are: the basketball court, the smoke pit, or behind the school where they smoke marijuana.

"My job is to just get right in there and let these guys know that what they're doing is harming themselves. But still be cool and approachable. Not lecturing, or naggy," she says. "Let's just talk, let's just hug it out, right?"

Art Steinman, who manages the program, describes SACY as being a "wrap-around" initiative that creates space for informed dialogue amongst children, families, and teachers.

"We want to turn down the angst, says Steinman, "Let's just calm down folks. And talk about it -- like we would other health issues."

Before SACY, children with substance problems were often punished with suspension or expulsion, according to Steinman.

"Kids thank us for treating them with respect. Treating them with dignity," says Steinman. "Not like some little 'druggie' who's got this problem and should go away. We draw them close. We support them."

Seven counsellors for 25,000 students

That support is stretched thin, given that SACY only has seven youth engagement workers to cover 25,000 students in the Vancouver School Board's 18 secondary schools.

Charlton, who splits her time between Templeton and Vancouver Technical, says that each would benefit from a full-time engagement worker.

Steinman wishes he could expand the program, but it has been difficult to find the funding. "There just aren't the resources," he says. "So it's hard enough to just sustain things, let alone see them grow and flourish."

In the past, the City of Vancouver did contribute a small amount of money to the program, according to Steinman. However, the provincial government is the primary funder of SACY, like other prevention initiatives in the City of Vancouver. The program's annual budget is just under $500,000, split between the school board and the health authority.

Although The Four Pillars is a municipal document, most of its recommendations are for other levels of government. Under prevention, the document recommends a citywide K-12 curriculum to be developed by the province, in consultation with several stakeholders including the City of Vancouver.

Despite the recommendation, Vancouver School Board has no standardized drug and alcohol curriculum. Teachers are able to use a variety of materials in their classrooms, including a list of resources recommended by the Ministry of Education.

The closest thing to standardized drug prevention is SACY, which reaches all of Vancouver's secondary schools. Donald MacPherson, author of The Four Pillars, lauds SACY for its pragmatic philosophy.

"It's one of the few programs that acknowledges 'gee, kids do drugs in schools'," says MacPherson, "and we probably shouldn't kick these kids out of school. We should probably work with them."

However, MacPherson fears that the program might be "on the cutting block."

"Those are often the kind of programs that go first," he says.

Steinman says the program is secure for the immediate future. However, it has suffered cuts. Over the past two years, SACY has been forced to lay off three employees (one in 2013/14, and two in 2012/2013). In total, it has the equivalent of 14 full-time employees.

Mental health a key factor

Young people who could gain the most from an expanded prevention program are those who use drugs or alcohol to deal with deeper struggles, say experts.

Professor Christopher Richardson at the UBC School of Population and Public Health argues that most of this substance use is simply experimentation, but those students with underlining mental illnesses are at risk of developing dependencies.

"You can almost think of it as self-medication. It might start off as experimentation. But they might find that it calms their anxiety or it helps slow the voices in their head."

Richardson suggests that prevention programs should teach all students about how to reduce the harms of substance use, but should be nimble enough to provide targeted mental health interventions for those students that are susceptible to substance abuse.

"There's a chunk of people with a vulnerability to addiction or emerging mental illness, and things can go really off the rails for their families. And they just get chucked from the system really quickly. They get dropped, and it's hard for them to get help," says Richardson.

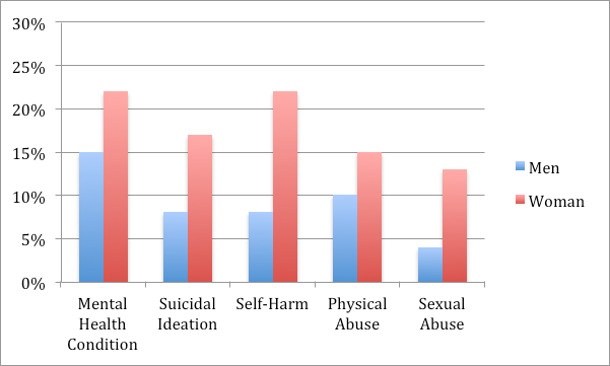

According to the B.C. Adolescent Health Survey, 22 per cent of females self-reported mental health conditions, while 15 per cent of men did. Of those who knew they had a mental health issue, 17 per cent did not seek out help when they thought they needed it. For Richardson, that is evidence that school prevention programs must also teach mental health literacy.

Charlton spends much of her time counseling students on their mental health. On the schoolyard at lunchtime, five Templeton students, all female, share stories of how had helped them when they struggled with depression and self-harm.

"I think she's supposed to be there just for drug and alcohol counseling," says one student. "But you can literally go there for anything. Like when I was feeling really depressed and suicidal, I would go to her right away."

Another young woman, who initially met Charlton in the hallways, says she booked a counseling session after her best friend had tried to commit suicide.

"Heather is always there when you need her," she says "I had a really tough time last year. One of my friends was in a really dark place in their life. I went to Heather with her, and she just helped both of us figure it out."

"It's crazy," adds another student, "because when most people want to talk to me, I just want to shut the doors and hide how I'm feeling. But with her, there's something about her that makes you want to open up."

Too little, too late?

Drug prevention researchers argue that programs like SACY should begin much earlier than secondary school. According to a large report released this summer by the Canadian Centre of Substance Abuse, there should be more early childhood programs that support parents to build healthy attachments with their children.

SACY has 2.8 full-time equivalent parent engagement workers who hold workshops for parents to help them understand the changes that their children are undergoing during adolescence. However, SACY does very little programming for younger families. Provided with more resources, Steinman says the first thing he would do is expand SACY into elementary schools.

In some elementary schools, WATARI facilitates a drug and alcohol awareness program called S.T.A.R., or 'stop, think, assess, respond.' In S.T.A.R. sessions, students role-play dangerous situations, like when a friend has alcohol poisoning or when somebody pressures them to use drugs.

However, the program only has two part-time facilitators. In the last year, they covered 22 of Vancouver's 74 elementary schools. There is a long wait list for the coming school year.

Prevention pillar: Does Vancouver make the grade?

When asked to grade the prevention pillar under Vancouver's Four Pillars, Fortin gave the city a C-, while Steinman gave it a C+.

Fortin argues that the small scale of prevention initiatives shows that B.C. puts more emphasis on the other three pillars, despite prevention being more cost-effective.

According to some research, investing one dollar in effective drug prevention can save a government between $14 to $37 in future health care costs. A 2002 report estimated that substance use costs the Canadian economy $39.8 billion dollars in a single year, when including both direct and indirect costs.

Donald MacPherson was even more critical than Fortin.

"I give prevention a D- because we have not got it through our heads that prevention is not about teaching kids who are already in high school about drugs," says Donald MacPherson, who is currently the director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition.

"Prevention is about daycare, early childhood learning; it's about resilience, it's about creating resilient families, and resilient communities. It has nothing to do with drugs," he adds.

Fortin says that prevention initiatives are cheaper than people might think. She told The Tyee that WATARI's S.T.A.R. program could cover all of Vancouver's elementary school children for around $350,000 per year.

As WATARI and SACY struggle to find resources to fund their programming, Fortin question's Vancouver's commitment to prevention. "So, what does it say? How much do our young people matter? Why do they have to become a problem to get supports and services?"

Next Thursday the series continues: How solid is the prevention pillar more than a decade after Vancouver, with other levels of government, committed to a more progressive approach to dealing with the drug dependency? ![]()

Read more: Health, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: