Like many people working in urban agriculture, the recent surge in interest caught me by surprise.

Last year it seemed as if an idea that had lingered for years on the fringe went mainstream, at least as an idea. People wanted to know all about getting started growing food.

Lawn-converters, community gardeners, food activists, small business growers and just regular folks with a hankering for a home-grown salad began seeing the city not as a jungle of buildings and cars but a countless number of small farms.

This year has been even crazier. The notion has spread so widely there's no longer any way to describe the typical aspiring grower. People of all ages, classes and backgrounds want to get involved. Mini-growing projects are sprouting up everywhere like mushrooms after a rain.

Apparently, it takes a crisis to raise an urban farmer.

There's also nothing quite like hunger to convince public officials that helping people grow their own food is good policy.

Digging into the past

The roots of the current popularity in community gardening in North America go back at least to the Economic Panic of 1893. Detroit then responded to the growing ranks of unemployed and restless urbanites by offering them vacant land to grow potatoes, turnips, beans and more.

The city invested $5,000 in the campaign, a lot for the time, but when it resulted in $28,000 worth of produce going to the people who needed it most, the idea quickly spread to New York, Philadelphia and other cities. The community gardening movement in North America was underway.

But not for long. Governments have always blown hot and cold on urban farming. In tough times, policymakers discover the time, energy and, crucially, the funds to make it work. But with the end of each crisis, official support typically wanes, and so do opportunities for the public to grow food.

Then comes another crisis and another start. In World War I the American government created the National War Garden Commission to help "soldiers of the soil" grow Liberty Gardens. The results were even better than expected.

Victoria's groundbreaking 1917 policies

Canadians were certainly up to the task, including those in our area. British Columbians have never been slackers when it comes to growing our own.

The spunky City Farmer website has an archived article by Shirley Buswell documenting urban growing campaigns that did fabulously well here during difficult times, only to be given up and nearly forgotten. It quotes the Victoria Mayor's Annual Report on the state of the city during a particularly hard period in World War I:

"Early in 1917, in view of the world-wide shortage of food stuffs, an active campaign was inaugurated by the City Council to stimulate production by means of cultivation of vacant lots and backyards. Briefly, the campaign was extremely successful; the response of the citizens was beyond expectation...

"...Much greater necessity exists for increased food production in 1918. All authorities agree that the world supply of food is reduced to famine conditions in many countries, and to within a fraction of the famine line in the most favoured localities. 'Every little bit counts,' and it is earnestly to be hoped that the response, in Victoria, of the 'Back-yard and Vacant Lot Brigade,' during 1918, will greatly exceed the excellent record of 1917."

Was it just tough times or were politicians back then also made of sterner stuff? The same article reports that the Victoria City Council went on in 1918 to persuade the provincial government to pass "The Greater Food Production Act."

Described as a "radical and progressive departure in legislation," the Act let cities take over vacant tracts of land to grow food without having to compensate the property owner.

52,000 Victory Gardens in Vancouver

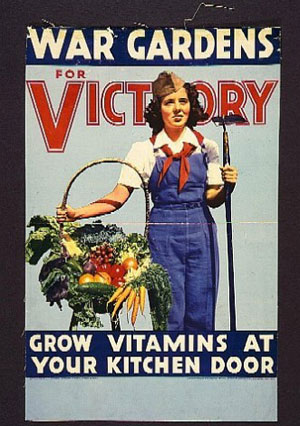

Government support for citizen farming dwindled after the war, only to be revived during the 1930s with a push for Relief Gardening to help residents survive the Great Depression. That was followed by another boost during World War II, as the Victory Garden campaign encouraged citizens to help the national effort by growing their own vegetables.

A Vancouver newspaper in 1943 counted 52,000 Victory Gardens in the area, each growing an average 550 pounds of vegetables. The total value of the food grown was estimated at $4 million.

And that amount may not have included eggs. Back in the 1940s, reports City Farmer, Vancouver residents could keep up to 12 chickens without a permit. Today, a modest proposal to allow a few backyard birds sent some city-slickers into a tizzy, but during the height of the grow-your-own fervor in the 1940s, even a dozen fowl wasn't enough for some. City Hall received dozens of permit requests from residents seeking larger flocks.

Yet again, when the war ended, official support withered, and so did opportunities for people to grow city food. This time, it was the global food system that was about to take over.

Rise of the monoculture crops

The industrial farm, which Chair of Food Secure Canada Cathleen Kneen calls "so 20th Century," was revving up to feed the world. The 1960s "green revolution" of chemical inputs on vast tracts of monoculture crops boosted production in a big way.

As food prices in rich countries dropped, the non-edible benefits of urban agriculture -- public education, social cohesion, healthy recreation, city greening -- were not deemed important enough to save much of the city farm land from development.

But every city has at least a few ardent growers who won't let go. Some public food gardens managed to hang on during the lean years of non-support. New immigrants continue to look incredulously at the amount of money and sweat people pour into their lawns, and wonder what it is about turf grass that they value over fresh snap peas or plump figs or pak choi. School gardens have been a feature in some cities for more than a century, although never to the level of their earliest days when they were considered a part of the curriculum as important as math and reading.

Interest in urban agriculture was rekindled in the 1970s when organic food entered the public consciousness. Community gardens also sprung up in sporadic places not just as food-growing spots but as neighbourhood enhancement projects. And for good reason: a recent study from the New York University School of Law found a community garden can raise nearby property values by as much as 9 per cent, increasing tax revenue to the city by $500,000 over 20 years.

Many of these projects were the result of long, determined efforts by civic-minded volunteers, either with the support or over the opposition of public officials.

BC's community garden renaissance?

In B.C., most public growing efforts outside the crisis periods have been self-generated campaigns by volunteers. That's left us behind cities such as Montreal and Toronto where government support was more readily available.

Vancouver could list about 20 community gardens by the year 2000. It may have about twice that number today, depending on how you count. Shared growing projects come in all types and on all kinds of land, not all of which get registered.

The increase is due in part to government interest. Former Vancouver City Councillor Peter Ladner is remembered fondly less for his call in 2006 for 2,010 new food-growing plots by the year 2010 (a grand statement that included no funding), but for his work on a bylaw exempting community gardens from city water bills.

Appropriately for an organic creation, community gardens are as diverse as the people who tend them, and no two look alike.

Collective farming projects today range from the tiny -- a pocketful of plots on an unused street end -- to a park-like spread divided three ways into an organic food plot area, a communal area with fruit trees, herb gardens and picnic spots, and a wildlife habitat area -- as in the model of the much-visited Strathcona Community Gardens.

A surprising number of mini-farms have recently been built with no city input on privately donated land, and may not be widely known.

Keeping an even lower profile are projects where food is being tended on land that wasn't exactly "donated" but "borrowed" by guerrilla gardeners. On that level, we have some of the most enthusiastic growers in the world.

Next Tuesday, part three of this series: When it comes to urban gardening and local food security policies, how does BC rate compared with other places? Find previous stories in this series here. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: